What I learned in Tallahassee

Sitting in air made frigid, I postulated, to keep us awake, we 528 attendees of Florida’s Boys [sic] State at Florida State University were told by various esteemed speakers that this was “the 73rd session of the Florida American Legion Boys State,” and that we were “the best and the brightest,” etc. Looking around, I didn’t feel like my fellow delegates had any particular quality in common that made them “the best of what Florida has to offer,” but I would later figure it out.

Delegates – male juniors in high school – come from across the state. We are organized into halls in the dormitory (cities, overseen by counselors) and floors (counties; two cities are in each), and are all citizens of one state (Smith Hall). We are in the state capitol to run for municipal, county, then state offices and run a mock government.

I expected much from the program, but not much from myself. I imagined ambitious, outgoing boys pandering for my vote with automatic smiles, firm handshakes and painfully deliberate body language. There was some of that, though not as much as expected.

My city’s mayor began campaigning for governor on the bus to Tallahassee. I expected myself to fail at Boys State, to settle for an easy-to-get position rather than to risk failure for the position I really wanted, because my smile is not automatic, my handshake is awkward – firm but sometimes too brief – and my body language is anything but statesmanlike. Fear restrains my ambition, while it emboldens my imagined colleagues’.

However, as my mother told me, I would not spend a week away on the dime of generous veterans to do any less than my best. Members of the American Legion, an organization for veterans, pay for the entire trip and provide transportation and spending money for the boys.

The maroon polos that delegates have to wear call it “Florida’s Premier Youth Leadership Program,” and the speakers who visited called it that in their speeches, but I did not understand how the program taught leadership, at least while I was there.

My city had two counselors, one who had been a counselor for a few years and one who was in our shoes a year before. On the last night, counselors give their delegates a certificate, a Boys State lapel pin, etc. As we sat on the floor of our hall, he explained that this ceremony was when he, his fellow counselor, and we, if we wished, would “open up.”

He knew something that I hadn’t quite grasped: most people, even at age 17, have suffered greatly and have something to open up about.

The counselors spoke, and so did we as we went up to get our certificates. We spoke of addiction to pornography, of coming out as gay, of attempted suicides, of faith, of homelessness, of dead parents and grandparents, of moving on.

Then, a few of us stayed up to argue about politics with the one of the counselors in their room, but the argument turned out to be more civil than I imagined. One counselor fell asleep on his bed, and I fell asleep on the other’s, slumped up against the wall.

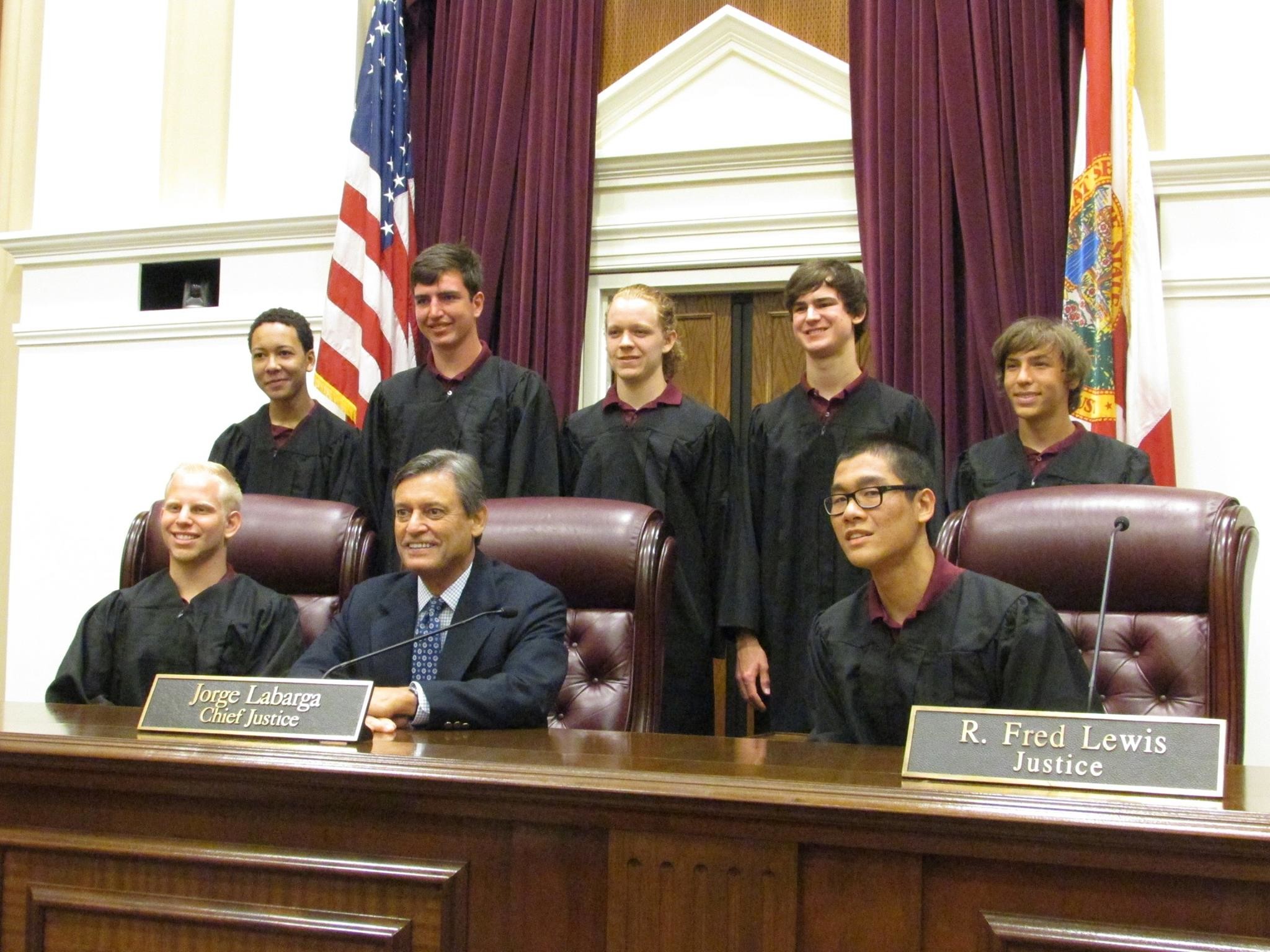

The fun I had at Boys State, exploring the Capitol, donning the robes of a Justice in Florida’s Supreme Court and general tomfoolery made the program worthwhile on its own. But the last night made me realize that people are, almost invariably, more complex and broken than they seem (or seem to me, at least).

The official activities of Boys State make it fun, but do not make it life-changing; the transformative nature of being stuck with a bunch of strangers for a week – strangers broken and torn by suffering, strangers who have endured more than what could seemingly fit into 17 years – makes the program life-changing.

To lead well, I learned, we must remember the incalculable suffering of others. This is no revelation, I know, but it took Boys State to make me realize that others aren’t as they seem. The true value of Boys State lies in that it puts boys together and helps them interact – children need that today, it seems, more than ever.