Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy petty officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

jack@claytodayonline.com

Celia E. Ochoa lives in Middleburg now, but it was nearly 30 years ago when she, her family and six other passengers were …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy petty officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

Celia E. Ochoa shares her story in memoir, 'Row Your Boat Cuban Refugee'

Celia E. Ochoa lives in Middleburg now, but it was nearly 30 years ago when she, her family and six other passengers were ankle-deep in the surf along Cuba’s northern coast, boarding a boat her father had soldered together from scrap metal.

Their boat embarked from Santa Cruz del Norte, a Cuban fishing town, at 2 a.m. on Aug. 22, 1994. More than 90 miles of pitch-black open ocean separated the family from the U.S. and their hoped-for freedom.

They were terrified, and rightfully so. While evading authorities in safe houses, Celia’s father spent months building the boat. He mounted an engine, but it would be a stretch to say that his creation would be in seafaring shape. The boat and motor weren’t tested. The Ochoa family wasn’t even sure it would float.

Still, for the family, this was a shot in the dark they had to take.

In her memoir “Row Your Boat Cuban Refugee,” Celia chronicles her life growing up and escaping Cuba in the grim aftermath of a family and national tragedy. Gen. Arnaldo Ochoa, a cousin to Celia’s father, was executed by the communist government.

Fidel Castro awarded Ochoa the Hero of the Revolution for his success in leading the Cuban contingency in the Angolan Civil War. Five years later, Ochoa, the highest-ranking general in Cuba, was accused of corruption, drug trafficking and treason.

The accusations shocked Ochoa’s family and the nation since he was indeed considered a hero to the Cuban people. He was beloved and applauded for epitomizing the ideals of the Cuban Revolution and the international socialist movement.

Clay Today was consulted by two professors for their expertise in the historical context.

“Arnaldo Ochoa was a decorated military leader and a rising star. The sentiment was he may have gotten too big for his britches,” Professor Michael Bustamante from the University of Miami said.

Ochoa was tied to Pablo Escobar and was accused of granting Escobar’s operation permission to station and pass through Cuba while skimming money off the top. It is still debated whether the accusations, trial and eventual execution were politically motivated.

“That’s the million-dollar question. Did he do it? Would he really have been able to coordinate such an operation without permission and acknowledgment from the higher-ups? There is a widespread perception that Ochoa was made to be the scapegoat. The trial was nationally televised and filmed in a weird, soap-opera-like way,” he said.

“The Ochoa trial was this ‘Stalinist’ thing,” Professor Lillian Guerra from the University of Florida said.

“It was chilling. It unmasked the true nature of the state for the millions of Cubans watching on live television,” she said.

It is widely accepted that on the day of his execution, Ochoa requested not to be blindfolded and to be able to give the command. Castro granted both requests. He faced the firing squad and gave the command on July 13, 1989.

Guerra said during the trial, protestors spray painted “8A” (Ocho-A for “Ochoa”) across city streets nationwide as a statement of solidarity, an act which also would have been considered treason.

Whether it was a way to quash an upcoming political rival or not, the consequence was permanent. The Ochoa family was struck with grief. Ochoa’s life, the family’s pride, was stolen from them in such a disgraceful way. The family was forced to carry on.

In her memoir, Celia wrote, “Sharing a last name with Gen. Arnaldo Ochoa was basically the equivalent of being branded with a target on your back.”

The Ochoa name, coupled with Celia’s father being a fugitive facing 20 years in prison, was why the family rushed and risked their lives to escape the communist government in Cuba. The only feasible escape off the island was by sea.

There's this profound moment in Celia’s memoir that occurs immediately after the family embarks from Santa Cruz del Norte. Worst-case scenarios pile up one after the other—seawater flooding the boat, the navigator dropping the compass into the sea and realizing they had been navigating in the wrong direction for hours—all while the lights lining Cuba’s coastline are still within eyesight.

Setback after setback, any other family would have seen this as a sign to turn the boat back to shore.

In an inspiring display of determination or desperation, Celia’s father took the helm, followed the North Star and pressed unflinchingly forward.

“There was no turning ‘back moment’ for my father. It was now or never,” Celia said later in an interview with Clay Today.

It was a decision that would change their lives forever.

Celia, her family and the six other passengers were not alone on the Florida Straits. They were joined by 35,000 “balseros,” the Spanish word for “rafters,” in what would be known as the “1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis.”

In her memoir, Celia describes her odyssey on the sea as she saw it at age six – a flotilla of rafts and wreckage headed to Florida.

The total number of Cubans who perished at sea is a disputed figure. For 1994, Guerra estimated the number to be in the tens of thousands.

A U.S. Coast Guard ship eventually intercepted the 10 passengers on the Ochoa boat and picked up hundreds of other stragglers as the ship made its rounds.

The Ochoa family once thought they would never see Cuba again, but the Coast Guard transported them back to the island.

But not back home.

The Detention Center

More than 30,000 refugees were sent to Guantanamo Bay, a “legal no man’s land,” University of Miami Professor Michael Bustamante said.

It isn’t formally U.S. territory and hasn’t been since 1903 when the Platt Agreement was signed, which set the conditions for the U.S. to withdraw from Cuba and recognize the country’s new independence following the Spanish-American War.

One of the conditions was a perpetual lease agreement of a “coaling station” for about $4,000 annually. Since the Cuban Revolution in 1959, the communist government, as a statement of protest, declined every check the U.S. sent annually (except for one that was reported to have been cashed in by accident).

Steamships have been long discontinued, but the United States still maintains control of the base. The U.S. exercises jurisdiction and de facto control while also insisting that Cuba retains sovereignty.

“Full constitutional rights do not apply in Guantanamo Bay, as we have seen during the War on Terror. The refugees did not have access to due process for immigration proceedings. However, Cuban-American lawyers tried and failed to remedy this in a lawsuit at the time,” Bustamante said.

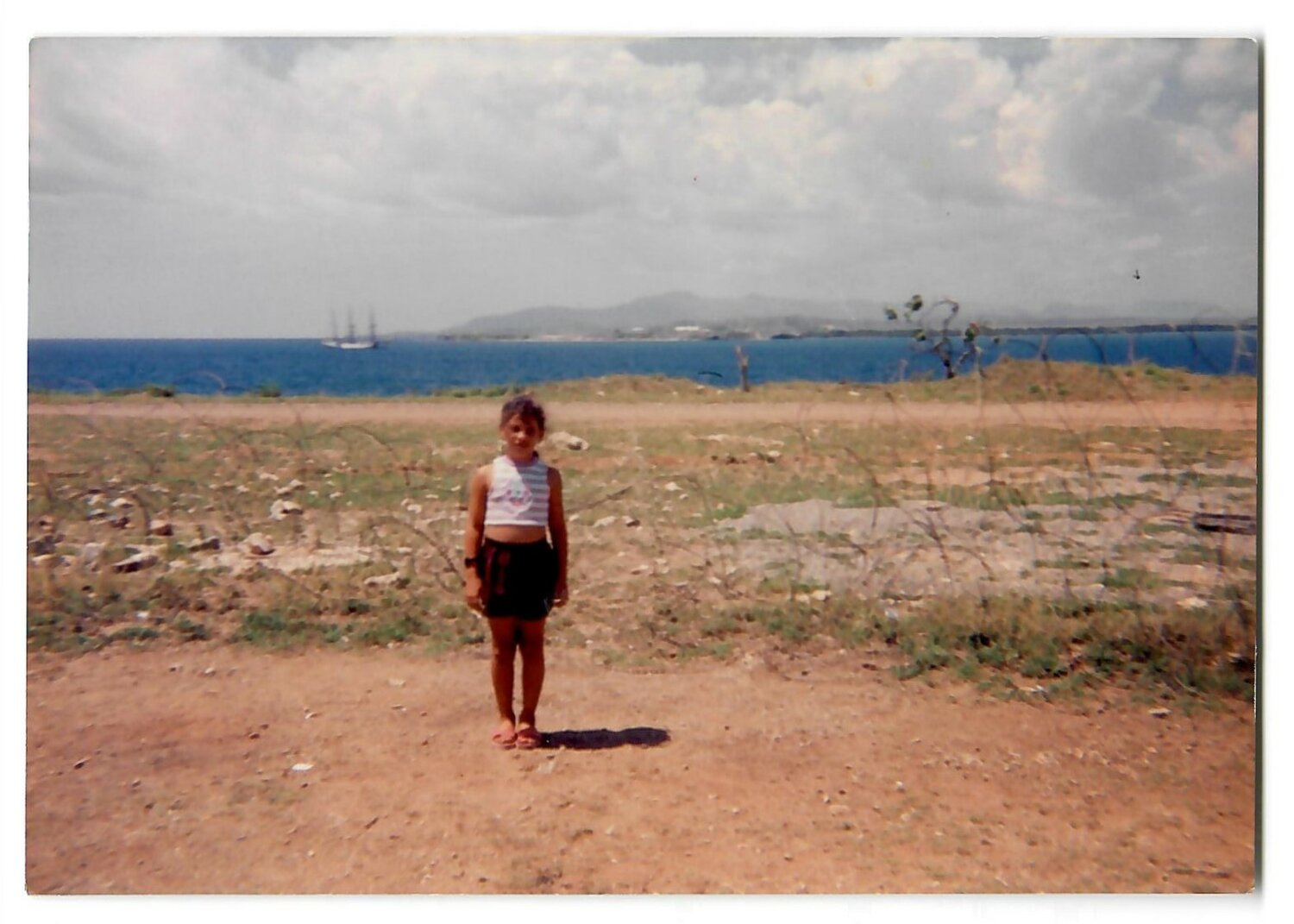

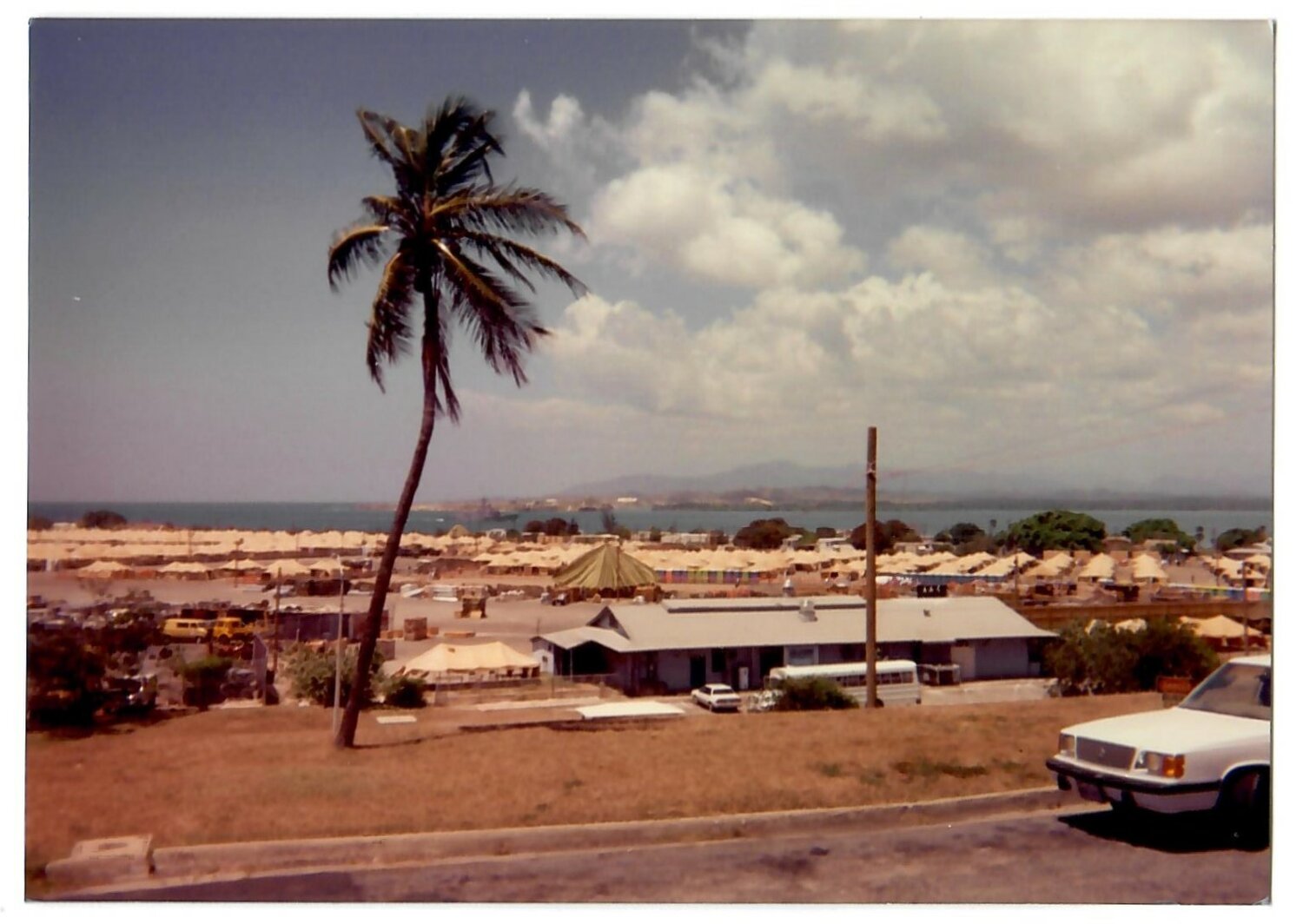

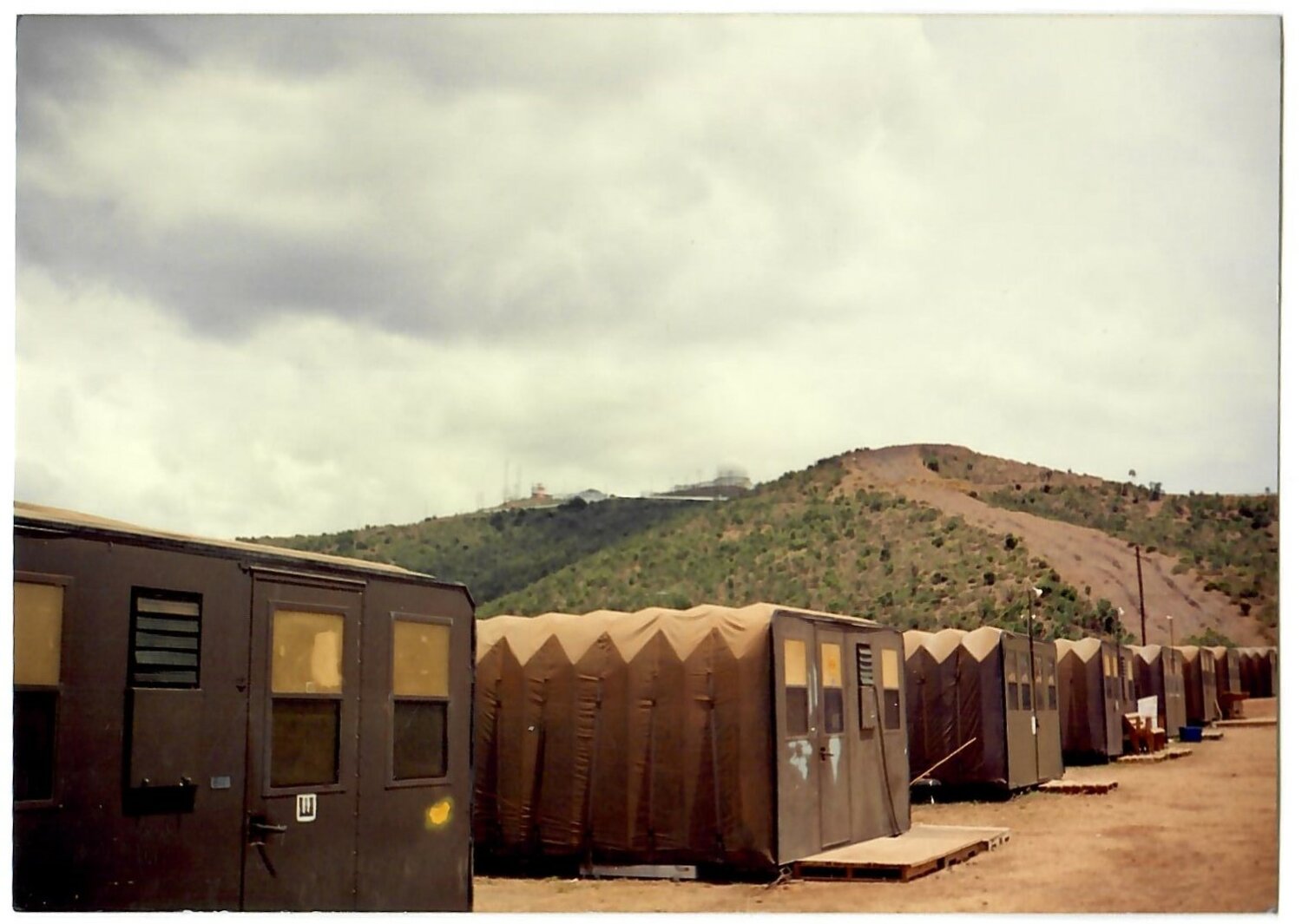

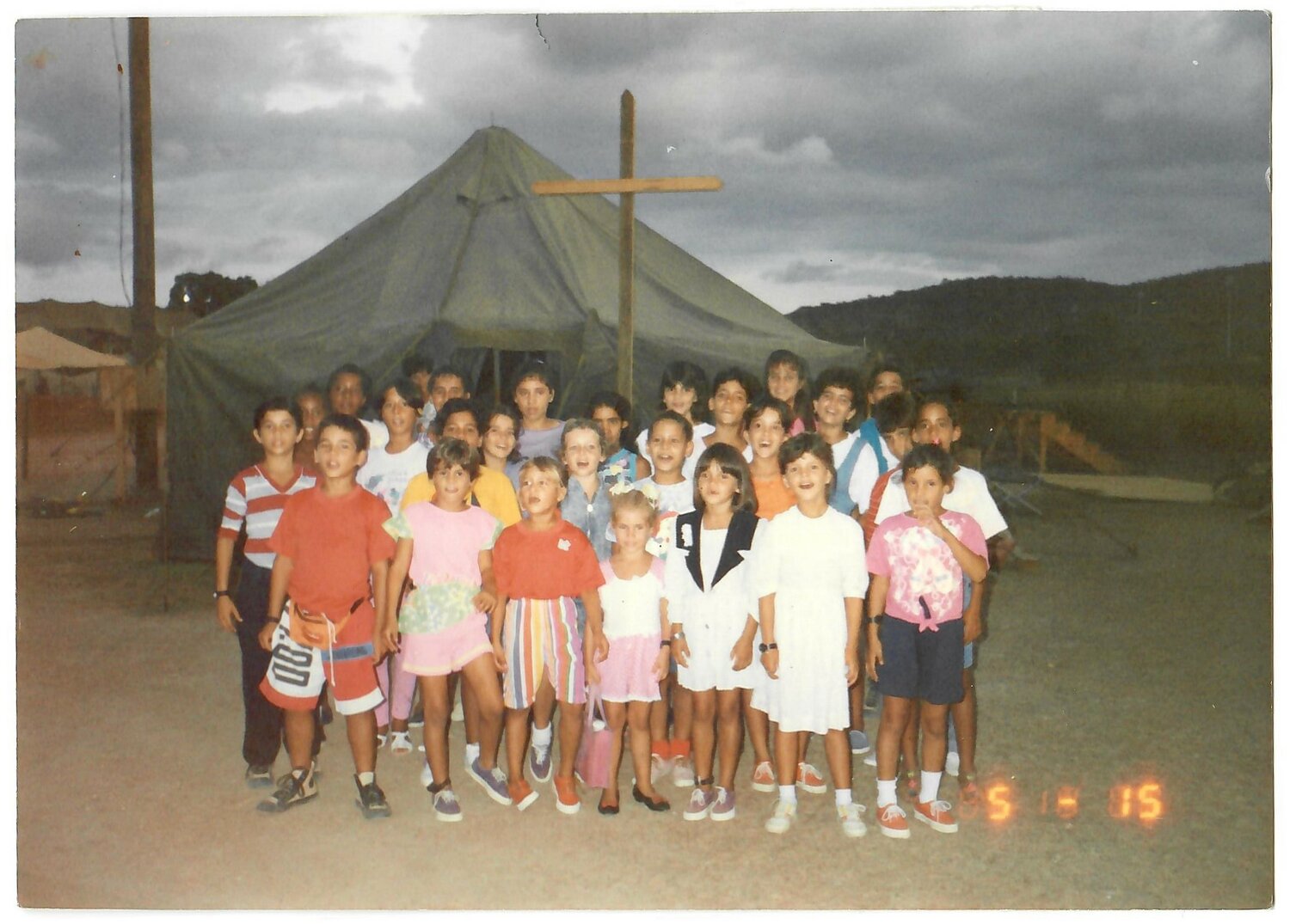

Celia shared slices of her childhood at Guantanamo Bay in her memoir: the sights, the sounds, the pain and even the small joys.

She empathized with the guards.

Tent camps were hastily erected. The U.S. officers scrambled about what to do. Celia was thankful for every meal, which was an improvement from the limited rations they received back home.

Celia said the guards tried to make the best out of the crisis. They went well out of their way to be accommodating, some even risking disciplinary action to bring extra supplies to the Ochoa family.

She was thankful for each act of kindness and disappointed in the other refugees for being so openly hostile.

“I do think the conditions were not ideal or acceptable. The camps eventually got better, but still, the refugees were treated more like a threat to United States security than like refugees,” Guerra said.

The refugees confined at the base had no idea what would happen to them. They couldn’t leave. They couldn’t call home.

At its most significant peak of confinement, it is estimated the camps held more than 30,000 Cuban and 30,000 Haitian refugees.

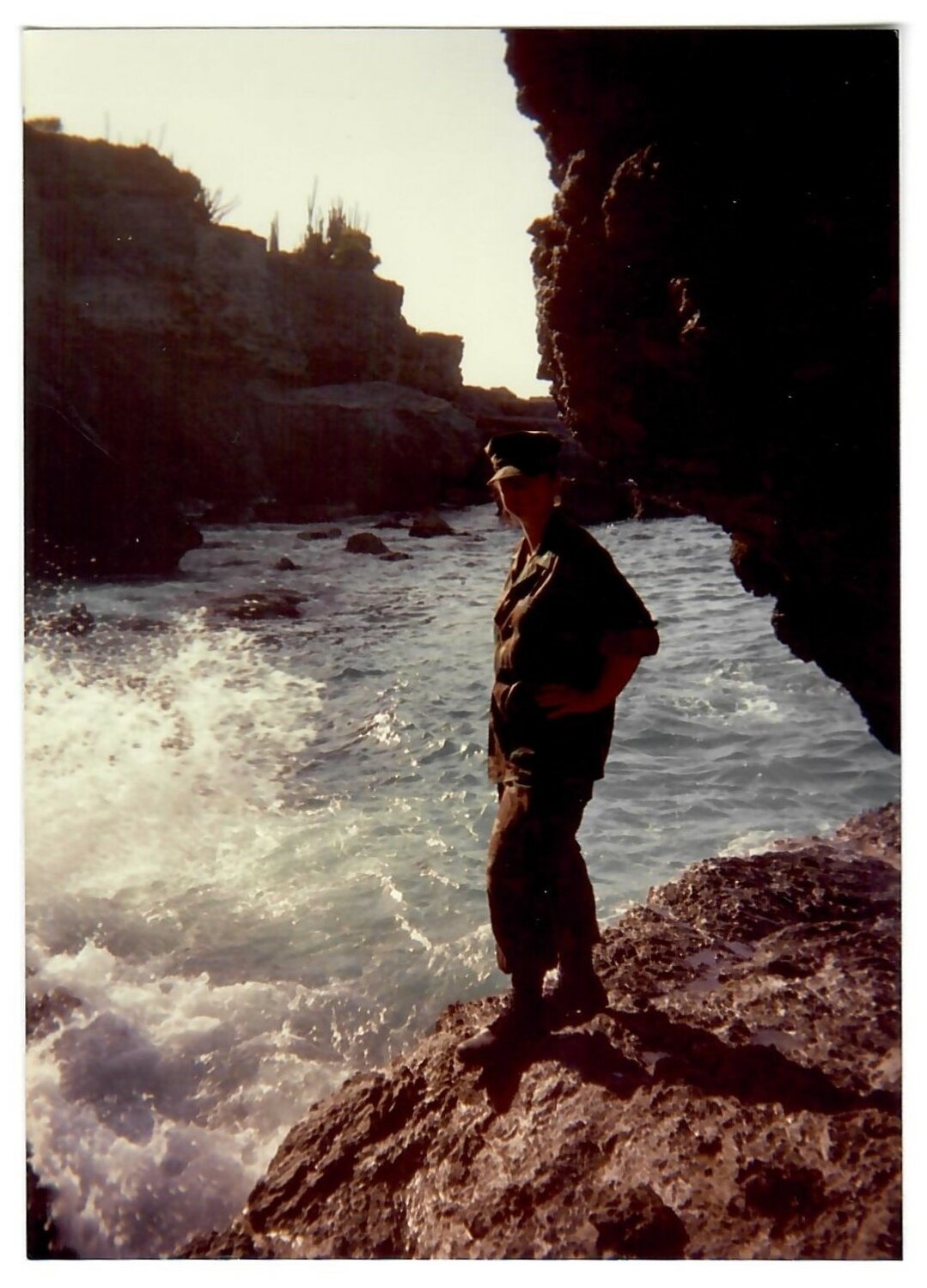

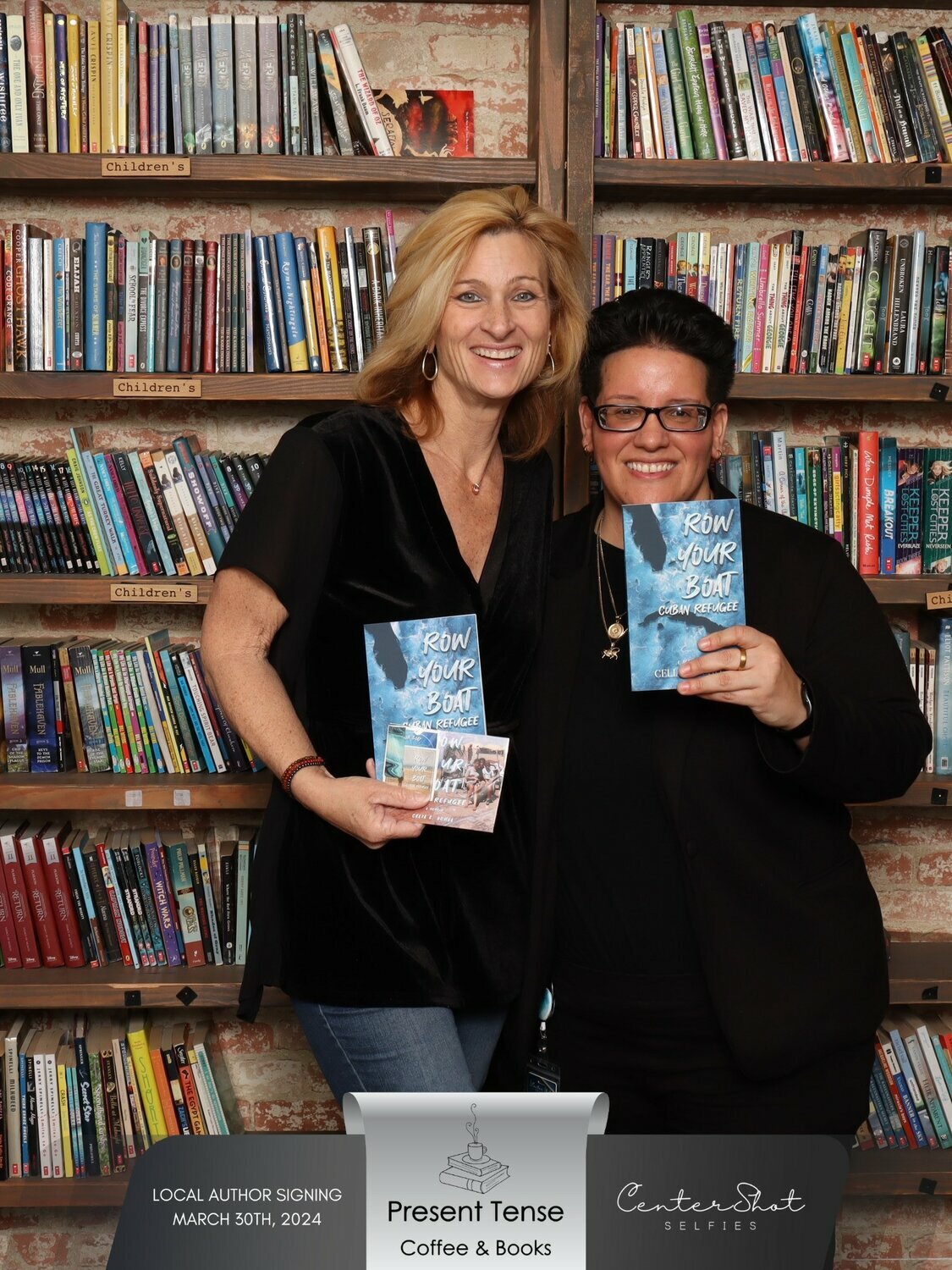

In 2023 and living in Middleburg, Celia self-published her memoir. As a courtesy to Clay Today, she shared a meticulously curated photo album, which included many photos within her memoir. Fittingly, she is the co-owner of Center Shot Selfies, a photo booth rental company.

On March 15, Celia worked at her photo booth at a Jacksonville Icemen hockey game. Tanya Lea and a friend approached the photo booth and posed for a few photos.

Tanya asked about her photo booth business and the events they cover.

“I told her we do weddings and birthdays, and I recently ventured into unique events such as book signings. As I was an indie author, I would bring the booth with me to these events. Naturally, she asked what my book was about. She ordered my book on the spot,” Celia said.

Of course, part of Celia’s experience as an Ochoa and a refugee involved a stint at Guantanamo Bay from 1994 to 1995.

Tanya was at Guantanamo Bay during the 1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis. The realization dawned on her.

“Oh my god, I fed you!” Tanya said.

The Pink Palace

On Friday, Feb. 5, 1993, Tanya Lee went by the name of Petty Officer Tanya Thompson. She was a cryptologic technical operator stationed at the Atlantic Intelligence Command.

That night, she left her evening shift early. She entered her bedroom only to realize she was not alone. A man was waiting for her with a gun drawn. She was beaten, raped and left for dead.

She started drinking as a way to self-medicate, along with other unhealthy coping mechanisms, as she became consumed by dark clouds of negative thoughts. She closed up and turned inward.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a mental illness commonly associated with the military, especially regarding frontline combat. It’s understood PTSD manifests from a variety of terrifying, life-threatening events. More than 90% of rape victims develop PTSD following an assault.

Tanya was diagnosed with PTSD, OCD and other diagnoses years later.

According to the DSM-5, a diagnostic tool for mental health disorders, symptoms of PTSD include intrusive memories, avoidance, negative changes in thinking or mood and changes in emotional reactions.

“I was afraid to go in through the door. My mom would be on the phone with me anytime I entered through the front door,” she said.

Living in the apartment was a source of constant psychological stress. Tanya requested a transfer as soon as she was able. She wanted to be transferred anywhere away from Norfolk, preferably somewhere international.

Her request was granted, and she left later that year.

The “North End Rapist,” identified later as Kerri Charity, was apprehended on Christmas Eve, 1993. His trial began in early 1995, running in tandem during Tanya’s subsequent deployment when she was stationed at “Gitmo,” the nickname for the U.S. Guantanamo Naval Base.

Tanya’s job at Gitmo was 9-to-5. To her, it was just another naval base in the Caribbean, where she lived and worked from 1994 to 1995.

“It feels like a lifetime ago as much as it feels like it happened yesterday,” she said.

Specifically, she worked at the “Pink Palace,” an on-base facility referred to that way for its size and hue.

She began each day by waking up at 6 a.m., before dawn, getting in her daily PT (physical training), and then getting to work.

She was responsible for installing a JDISS (Joint Deployable Intelligence Support System), which allowed communication between the Atlantic Intelligence Command and Naval Station Guantanamo Bay.

As a junior officer, she was assigned collateral responsibilities as well. Most notably, she helped feed the refugees – thousands of men, women and children. The refugees held out their plates as they moved through the cafeteria line.

One scoop of rice. One scoop of red beans. A spoonful of peanut butter, if they were lucky.

Tanya and the others on the kitchen crew couldn’t talk or take photos of the refugees. Most spoke Spanish, anyway.

Tanya was a server during one of the “food riots” that Celia mentions in her memoir. The refugees would throw the food back at the servers, and Tanya honestly couldn’t blame them.

Refugees, military personnel and contractors put tabs in their water to make it potable. Still, many refugees contracted tapeworms and other parasites. Celia and Tanya both empathized with the refugees.

‘“They ate the same (stuff) every day. While also drinking water that was unsanitary. The guards had to break up a riot where refugees were throwing food. I don’t blame them. They really did eat the same (stuff) every day for every,” she said.

Her deployment at The Pink Palace was briefly interrupted by the rape trial. Charity was sentenced to seven life sentences plus 80 years.

It was a moment of celebration for Tanya and the other four women. It was a moment of relief knowing that another woman would not be victimized by him again. However, healing took longer. And forgiveness came even harder.

“Tragedy changes people. Forgiveness was the hardest thing. I knew I needed to forgive, but it was so hard for me,” Tanya said.

While Celia experienced physical confinement at Guantanamo Bay, Tanya’s shackles were mental. Feelings of guilt, shame and anger followed her around the world. She still felt responsible for what happened to her, and she experienced imposter syndrome at her new job. She threw herself into her work. She was frequently photographed staring somberly out along the fences by the cliffs.

Celia’s pain came from another kind of shame. She was being punished in her homeland by a country she thought would embrace her. Her hope for freedom was replaced by barbed wire, a steady diet of beans and rice, dysentery and humiliation.

“I was running away. We (Tanya and Celia) were both running away.”

Impromptu meeting stirs memories, creates questions about time together

With it being nearly 30 years ago, Celia E. Ochoa can’t say if Tanya Lea dropped a scoop of rice for them. Or a scoop of beans. Or handed her and her family MREs (meals ready to eat).

Tanya can’t say for certain after reading the memoir and viewing each image.

But considering the odds it took to bring the women to the base in the first place, Celia thinks it was not unlikely they would have crossed paths. Her family moved around the base, and it’s not like they had other food options.

Celia currently lives in Middleburg with her wife. They have four children: two boys and two girls. Together, they own Center Shot Selfies, LLC, a photo booth rental company. The small business is an active Clay County Chamber of Commerce member.

Celia wrote her memoir hoping that someone – a guard, a refugee, a friend and anyone else she met along her way – would reach out from that time in her life.

By that metric, the memoir was a success just one year after its publication.

Tanya currently lives in Jacksonville and co-owns Consciously Aware Coaching and Consulting. Tanya made it her life mission to educate and understand the depth of human emotion and behavior, having struggled with her own for years. She is passionate about helping people see the “light at the end of the tunnel” and turn their tragedy and trauma into victory and triumph. She earned an M.A. in Mental Health Counseling, an MBA, and a Ph.D.

Tanya was the keynote speaker at Finally Friday, an event sponsored by the Clay Chamber, where she spoke about the assault and her struggle with mental health publicly for the first time.

Tanya met Celia one month after her speech in just another coincidence.

Center Shot Selfies partnered with the Jacksonville Icemen. Celia’s wife was handing out extra tickets at a Clay Chamber meeting when Tanya’s friend accepted the tickets and brought Tanya along. They stopped by the photo booth to take photos and say, “Thank you.”

The “eureka” moment outside the Jacksonville Icemen game was solace and compassion.

Celia held respect for the guards and was thankful that, for her family, they did the best they could in an impossible situation. Lea resonated with the refugees and was impressed with their resilience against insurmountable odds.

Despite being on "either side of the fence" at Guantanamo Bay, the two women share much in common. Both women served in the U.S. Navy. Both women became entrepreneurs. Both have their businesses listed in the Clay County Chamber of Commerce.

Instead of giving into despair during what was for both a brutal, uncertain time in their lives, the two women clung to hope and chose compassion instead. Their respective inspiring stories show that even during physical or mental captivity, compassion is a choice we always have. Compassion comes from anywhere.

Epilogue

While the 1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis would be the last major waterborne migration crisis, its aftermath led to adopting the “wet foot, dry foot” policy – Cubans who managed to make it to shore (dry foot) were granted U.S. citizenship. However, Cubans who were intercepted at sea (wet foot) were turned away.

Cubans continued to voyage across the Florida Straits for various reasons, usually in risky makeshift rafts without engines. The continuing U.S. embargo, which had lasted for decades, coupled with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, led to unbearable economic hardship. The Soviet Union sent the equivalent of about $4 billion in aid to Cuba, aid that Cubans could no longer count on in the 1990s.

The “Maleconazo” protest, which Celia describes in her memoir as occurring ahead of the 1994 crisis, was the largest anti-government demonstration Cuba had seen since the Cuban Revolution.

The wet foot, dry foot policy was in effect from 1995 to 2017. The U.S. continues to permit 20,000 immigration visas annually for Cubans.

There is a circulating American sentiment viewing Cuba as a sort of “Caribbean time capsule.” Because of the embargo, Cuba is known for the antique American cars that still drive through its streets, usually by its state-operated taxi industry. Despite the decades-long embargo, U.S. history is explicitly tied to the island.

Domestically, Cubans make up a sizable ethnic group in Florida. Most Cuban Americans live in Florida; according to the U.S. Census, 6.5% of Floridians can trace Cuban ancestry.

Ending the wet foot, dry foot policy in 2017 did not end Cuba’s migration crisis. Instead, it manifested differently.

Shortly after reopening its borders following the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuba agreed with Nicaragua to freely allow travel between the countries without visa requirements.

Sen. Marco Rubio, the son of Cuban parents, considered the agreement to be a hostile act.

“The Ortega-Murillo regime (Nicaragua) is aiding the Cuban dictatorship by eliminating visa requirements to instigate mass migration to our southern border,” Rubio said in 2021.

Since 2021, it is estimated more than 500,000 Cuban refugees have flown from Cuba to Nicaragua and have traveled north to the U.S.-Mexico border. Guerra estimates the number of refugees to continue growing to one million by 2026, making the 2020s the latest and most present migration crisis since 1959.