Celebrate Clay County history: The Patriot’s Rebellion

CLAY COUNTY – The year 1812 brought a tidal wave of unrest to Northeast Florida. A group of “Patriots” mounted a rebellion against Spain in hopes of making East Florida a territory of the …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Celebrate Clay County history: The Patriot’s Rebellion

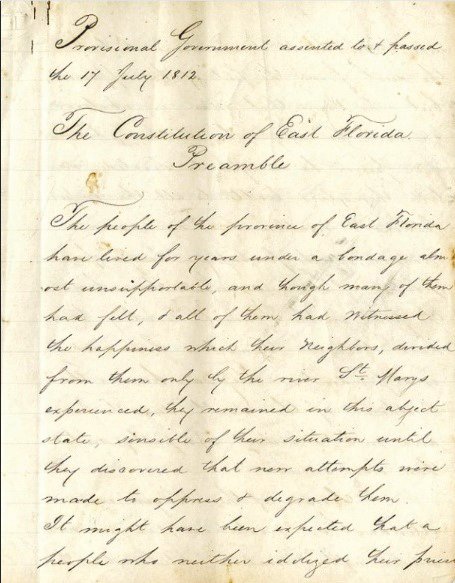

CLAY COUNTY – The year 1812 brought a tidal wave of unrest to Northeast Florida. A group of “Patriots” mounted a rebellion against Spain in hopes of making East Florida a territory of the United States.

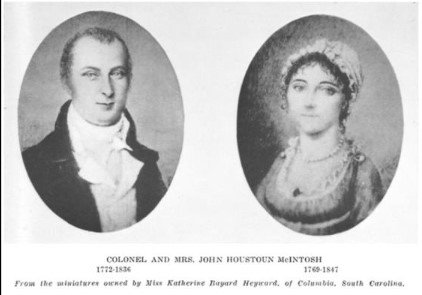

Their leader was John Houstoun McIntosh, not to be confused with his first cousin, Gen. John Houstoun McIntosh, the Revolutionary War hero. McIntosh had a close link to Clay County having bought Laurel Grove from Zephaniah Kingsley. Kingsley bought McIntosh’s plantation on Ft. George Island, and today it is the Kingsley Plantation National Park. McIntosh Avenue in Orange Park bears his name.

McIntosh was loyal to the United States, and he and his fellow Patriots gave Spain a headache for a few years. The rebels also had the backing of the country’s fourth president, James Madison. Word spread that McIntosh was elected the “president of the new territory” of East Florida. However, this was complete fiction – a concept mostly entertained in the rebels’ minds.

The raid on Fernandina, however, was not fiction. Backed by a U.S. gunboat and troops, the “Patriots” took the Spanish fort located there. The plan was to march to St. Augustine, take over the capital of Spanish East Florida and offer it up to the United States. This plot was foiled, though, when the Creek Indians and the Free Black Militia, who were allied with Spain, routed the rebels on their way there. The rebels were forced to retreat.

This maneuver created an international scandal. President Madison got cold feet and quickly distanced himself from the affair, which ultimately resulted in the Patriots losing the support of the United States. This started an earnest letter-writing campaign by McIntosh to the President and Secretary of State. McIntosh basically called them out and continued to ask for help and support. He pointed out the slaves would revolt, that East Florida would become a refuge for runaway slaves and that the Creek Indians would continue to raid with impunity. He emphasized the value of East Florida and what an asset it would be to the United States.

He reminded the president that he and the other Patriots had stuck their necks out. It was a 19th Century version of the Cuban Bay of Pigs incident. He even signed his letters, “President John Houston McIntosh.” His efforts were futile.

Spain was eager to squelch the rebellion and offered the rebels amnesty and pardons. McIntosh was leery of the offer and continued to believe that his assets would be seized. Spain did grant him amnesty, but his actions left him a marked man. He was repudiated by the United States, a country to whom he had lent his patriotism, and was now a traitor in Spain’s eye. The Spanish governor of East Florida, realizing McIntosh was a person of importance, let him leave Florida unscathed. McIntosh retired to his Georgia plantation. He later served in the First Seminole War.

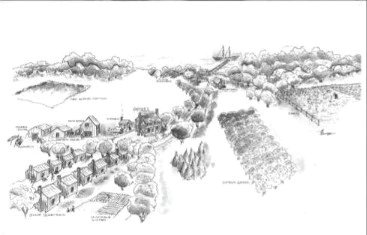

The rebellion caused a crime wave in the area. Some of the Patriots were not truly loyal to Spain or to the United States, only to themselves. These folks were bandits bent on raiding and marauding plantations and homes along the St. Johns and St. Mary’s rivers. Zephaniah Kingsley decided to fortify his plantation, Laurel Grove (now the Town of Orange Park). In particular, he fortified the main house, which was a combination of a store on the first floor and a residence on the second floor. He built a stockade around the building and placed cannons facing out towards the river.

Inevitably, Laurel Grove was raided by the bandits, who set up the main house as headquarters. Anna Kingsley, who was married to Zephaniah and had her plantation directly across the river, was worried about her children and slaves at Laurel Grove. She feared everyone would be kidnapped and sold into slavery.

It was Nov. 22, 1813, when Anna decided to do something about it. Spanish commander Jose Antonio Moreno’s orders took him to Doctors Lake in search of bandits to take back Laurel Grove.

He saw a canoe with Anna Kingsley aboard rowing his way. The canoe was coming from Laurel Grove’s dock. Once aboard Moreno’s gunboat, Anna ascertained it would be a safe place for her children and slaves, so she transported those people to the ship. To show her fealty to Spain, a county that recognized her, a former slave, as a free and whole person.

Anna proposed to burn down the main house and deny the bandits shelter. And, once given approval, she did just that. She snuck over to the house, set off incendiary materials inside and burned it to the ground.

In his report, Moreno wrote of Anna, “I cannot help but recommend this woman, who has demonstrated a great enthusiasm concerning the Spaniards and extreme aversion to the rebels, being worthy of being looked after, since she has worked like a heroine, destroying the strong house with the fire she set so that the artillery could not be obtained, and later doing the same with her own property.”

At the time of the burning, Anna Kingsley was only 20. Spain rewarded her loyalty with a 350-acre land grant.