Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

Celia E. Ochoa shares her story in memoir, 'Row Your Boat Cuban Refugee'

jack@claytodayonline.com

This is the first part in a four-part series telling the story of two women who were at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba during the 1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis. Celia E. Ochoa was a Cuban refugee. Tanya Lea was a …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Cuban refugee, U.S. Navy officer reunite 30 years after Guantanamo Bay

Celia E. Ochoa shares her story in memoir, 'Row Your Boat Cuban Refugee'

Celia E. Ochoa lives in Middleburg now, but it was nearly 30 years ago when she, her family and six other passengers were ankle-deep in the surf along Cuba’s northern coast, boarding a boat her father had soldered together from scrap metal.

Their boat embarked from Santa Cruz del Norte, a Cuban fishing town, at 2 a.m. on Aug. 22, 1994. More than 90 miles of pitch-black open ocean separated the family from the U.S. and their hoped-for freedom.

They were terrified, and rightfully so. While evading authorities in safe houses, Celia’s father spent months building the boat. He mounted an engine, but it would be a stretch to say that his creation would be in seafaring shape. The boat and motor weren’t tested. The Ochoa family wasn’t even sure it would float.

Still, for the family, this was a shot in the dark they had to take.

In her memoir “Row Your Boat Cuban Refugee,” Celia chronicles her life growing up and escaping Cuba in the grim aftermath of a family and national tragedy. Gen. Arnaldo Ochoa, a cousin to Celia’s father, was executed by the communist government.

Fidel Castro awarded the Hero of the Revolution to Ochoa for his success in leading the Cuban contingency in the Angolan Civil War. Five years later, Ochoa, the highest-ranking general in Cuba, was accused of corruption, drug trafficking and treason.

The accusations shocked Ochoa’s family and the nation since he was indeed considered a hero to the Cuban people. He was beloved and applauded for epitomizing the ideals of the Cuban Revolution and the international socialist movement.

Clay Today was consulted by two professors for their expertise in the historical context.

“Arnaldo Ochoa was a decorated military leader and a rising star. The sentiment was he may have gotten too big for his britches,” Professor Michael Bustamante from the University of Miami said.

Ochoa was tied to Pablo Escobar and was accused of granting Escobar’s operation permission to station and pass through Cuba while skimming money off the top. It is still debated whether the accusations, trial and eventual execution were politically motivated.

“That’s the million-dollar question. Did he do it? Would he really have been able to coordinate such an operation without permission and acknowledgment from the higher-ups? There is a widespread perception that Ochoa was made to be the scapegoat. The trial was nationally televised and filmed in a weird, soap-opera-like way,” he said.

“The Ochoa trial was this ‘Stalinist’ thing,” Professor Lillian Guerra from the University of Florida said.

“It was chilling. It unmasked the true nature of the state for the millions of Cubans watching on live television,” she said.

It is widely accepted that on the day of his execution, Ochoa requested not to be blindfolded and to be able to give the command. Castro granted both requests. He faced the firing squad and gave the command on July 13, 1989.

Guerra said during the trial, protestors spray painted “8A” (Ocho-A for “Ochoa”) across city streets nationwide as a statement of solidarity, an act which also would have been considered treason.

Whether it was a way to quash an upcoming political rival or not, the consequence was permanent. The Ochoa family was struck with grief. Ochoa’s life, the family’s pride, was stolen from them in such a disgraceful way. The family was forced to carry on.

In her memoir, Celia wrote, “Sharing a last name with Gen. Arnaldo Ochoa was basically the equivalent of being branded with a target on your back.”

The Ochoa name, coupled with Celia’s father being a fugitive facing 20 years in prison, was why the family rushed and risked their lives to escape the communist government in Cuba. The only feasible escape off the island was by sea.

There's this profound moment in Celia’s memoir that occurs immediately after the family embarks from Santa Cruz del Norte. Worst-case scenarios pile up one after the other—seawater flooding the boat, the navigator dropping the compass into the sea and realizing they had been navigating in the wrong direction for hours—all while the lights lining Cuba’s coastline are still within eyesight.

Setback after setback, any other family would have seen this as a sign to turn the boat back to shore.

In an inspiring display of determination or desperation, Celia’s father took the helm, followed the North Star and pressed unflinchingly forward.

“There was no turning ‘back moment’ for my father. It was now or never,” Celia said later in an interview with Clay Today.

It was a decision that would change their lives forever.

Celia, her family and the six other passengers were not alone on the Florida Straits. They were joined by 35,000 “balseros,” the Spanish word for “rafters,” in what would be known as the “1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis.”

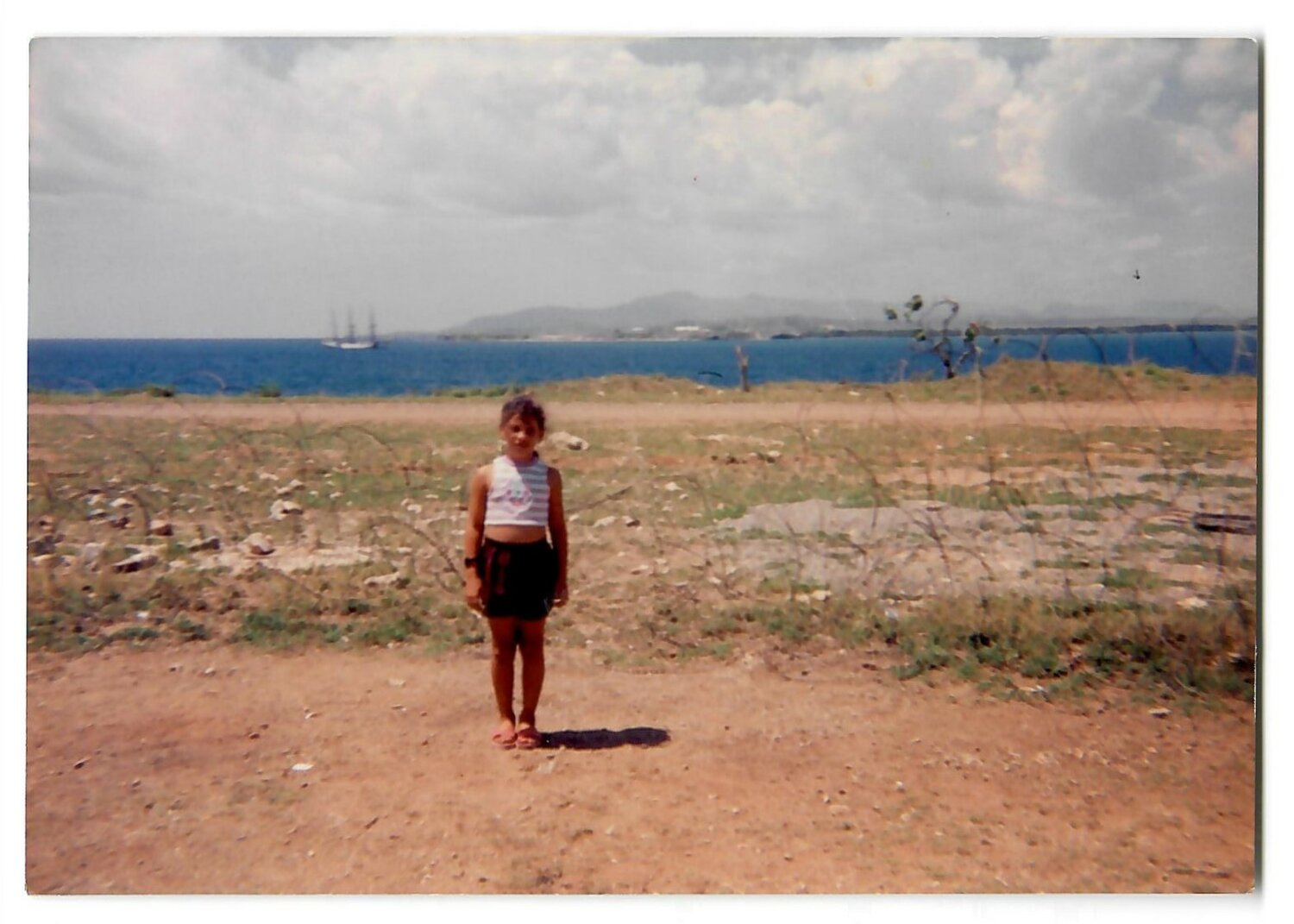

In her memoir, Celia describes her odyssey on the sea as she saw it at age six – a flotilla of rafts and wreckage headed to Florida.

The total number of Cubans who perished at sea is a disputed figure. For 1994, Guerra estimated the number to be in the tens of thousands.

A U.S. Coast Guard ship eventually intercepted the 10 passengers on the Ochoa boat and picked up hundreds of other stragglers as the ship made its rounds.

The Ochoa family once thought they would never see Cuba again, but the Coast Guard transported them back to the island.

But not back to their homes.

Next week follows Celia's experience in the "legal no man’s land” – The Detention Center at Guantanamo Bay.