Celebrate Clay County History

Maude Burroughs Jackson: In her own words

As we celebrate Black History Month, Clay Today and the Clerk of Court and Comptroller’s office have created a three-part series on Civil Rights Icon Maude Burroughs Jackson.MIDDLEBURG – …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Celebrate Clay County History

Maude Burroughs Jackson: In her own words

As we celebrate Black History Month, Clay Today and the Clerk of Court and Comptroller’s office have created a three-part series on Civil Rights Icon Maude Burroughs Jackson.

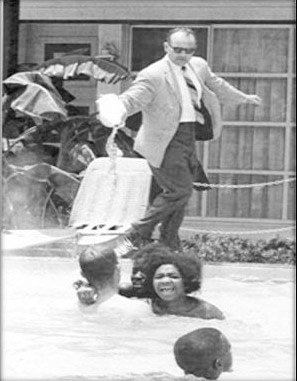

MIDDLEBURG – From May 1963 until July 1964, protesters in St. Augustine endured physical beatings and verbal assaults. They did not fight back, however, based on Dr. Martin Luter King Jr’s explicit non-violence instructions at the time.

By suffering through the violence and hate-filled rhetoric that embodied our nation’s Civil Rights Era, the protesters’ ability to literally turn the other cheek garnered national sympathy. This was a major factor in the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A young woman from Clay County bravely marched in St. Augustine with those protestors, met Dr. King, and went on to inspire generations.

Maude Burroughs Jackson was interviewed by Clay Today’s Mary Jo McTammany during January and February of 2007. This is her story in her own words:

“I was with Dr. King in ’63 and ’64 when he came down to St. Augustine on occasion. I started working with The Movement in St. Augustine sometime in 1962. I was in college in St. Augustine at Florida Memorial. I started there in 1960 and graduated in 1964. When I started, three of us were in school there at the same time – my sister Ann, my brother Eddie and I. We all commuted to class. I never lived in the dormitories at Florida Memorial. I met a family in St. Augustine, and it so happened that their pastor knew my family. The pastor taught one of my brothers back in the ‘30s, and he knew the name Burroughs, and he had talked about us to people in St. Augustine. When I met this family, she recognized our name and made me welcome to be a part of her family and stay during the school term in her home.”

“About 1962, I learned about the local Movement. I participated in all the sit-ins and marches. I went to headquarters a lot. Our headquarters was at Dr. Robert Hayling’s office. He has since moved from St. Augustine. There is a great story about him being in St. Augustine. He was in business there – a dentist. He had some terrible experiences trying to integrate St. Augustine. Some things I don’t think he even wants to talk about. I guess that’s why not too much has been written about St. Augustine and the Movement there. I met him by going to the mass meetings and by going to the sit-ins at Woolworths. I’m not too clear on exact dates, but I was deeply involved in all the sit-ins and demonstrations during ’62, ’63, ’64. The only exceptions were when I was at home in Middleburg during the summers.”

“We would go and sit at the lunch counter at Woolworth’s, and the waitresses would just keep walking past us. Every now and then, a waitress would say, ‘We don’t serve (racial slur) here.’ I know what that word means, and maybe, coming through the Movement, it doesn’t hurt me as much these days as it did then. So if I use the word, don’t feel hurt about me using it. It doesn’t really bother me if I use it because I’m using it in the context of how it was used back in the day. It did hurt during that time. In those days, ladies of quality – black or white – dressed nicely to go to town. The demonstrations and sit-ins were no different. I would have worn a nice skirt and blouse or a nice dress with hose and heels, with my nails done and my hair would have been combed. I probably looked much nicer than I would dress to go to town today. Times have changed. Also, being from 19 to 21 years old, I was very concerned about the way I was dressed. We were raised to be that way.”

“At the sit-ins, we always sat down in an orderly way because that was part of the instruction when you wanted to be a part of Dr. King’s Movement. There were very precise and detailed instructions on how to go out and how to conduct yourself while you were out, and no matter what people said to you, you were not to respond in any ugly way.”

“There was a group that was in charge of the Movement in St. Augustine, and I got involved by just going and sitting at the office, typing letters, sending out information about the Movement, and talking to people who didn’t want to go out on the marches. I would be left there to handle the office many times during those early marches. At that time, there might have been 15-20 people who would be there to organize things before the marches. They always reminded people to be on their best behavior, and that (they) might encounter people who would make remarks that would upset (them). They might throw things at you. They might hit you. They might spit on you. They might do anything to you, and you must not respond. Anybody who could not accept this – could not participate. So you already knew what to expect. You knew to expect doors closed in your face, skipping you in line; anything of that nature might happen to you.”

“Then, Dr. King started coming down (St. Augustine). The first time that I saw Dr. King, he came in for a mass meeting, and I stayed there at the office to take care of answering the phone or to take care of anything else that came up. He was getting in so late, and after the meeting, it was going to be so late that you wouldn’t dare try to go to a restaurant or anything. So, I was asked to prepare dinner for him that night at the office using a small toaster oven. I made a steak for him and toast and a little salad. And I got a chance to just sit and be in the inner circle of the leaders of the Movement. He was such a compassionate, such a common person – you just felt good being around him. A man of this importance, but every one of us was treated like we were the special one. And he showed so much respect for all of he participants – for everybody. It wasn’t like you were just a little person here in St. Augustine. He didn’t treat you that way.

“After that, when he began coming to St. Augustine on a regular basis – I spent a lot of time with Dr. King. Sometimes he would fly in and have to fly right back out. All of us spent time with him just working around the office and organizing the meetings. Some of us even went out to the high school with him and recruited children to participate. Dr. King didn’t necessarily come to all the mass meetings, but he did the marches. At night, we did the marches while the picketing and sit-ins were done during the day.

“After a mass meeting where Dr. King gave a fiery sermon – we sang “God Will Take Care of You” and just felt all fired up and ready to save the world. Sometimes, Abernathy or sometimes Andrew Young might be the speaker. All of them came to St. Augustine – C.T. Vivian, Y.T. Walker, Josea Williams, John Lewis. I got the opportunity to be around all these people. All of them didn’t come at the same time; they kind of cycled in and out. It was very well planned. One would leave, and another would come in to help with the Movement. (The) presence of the national leaders really was intended to generate national media interest. Local people could not get that kind of attention.”

Next week: The price of freedom.