The Orange Park Normal and Industrial School

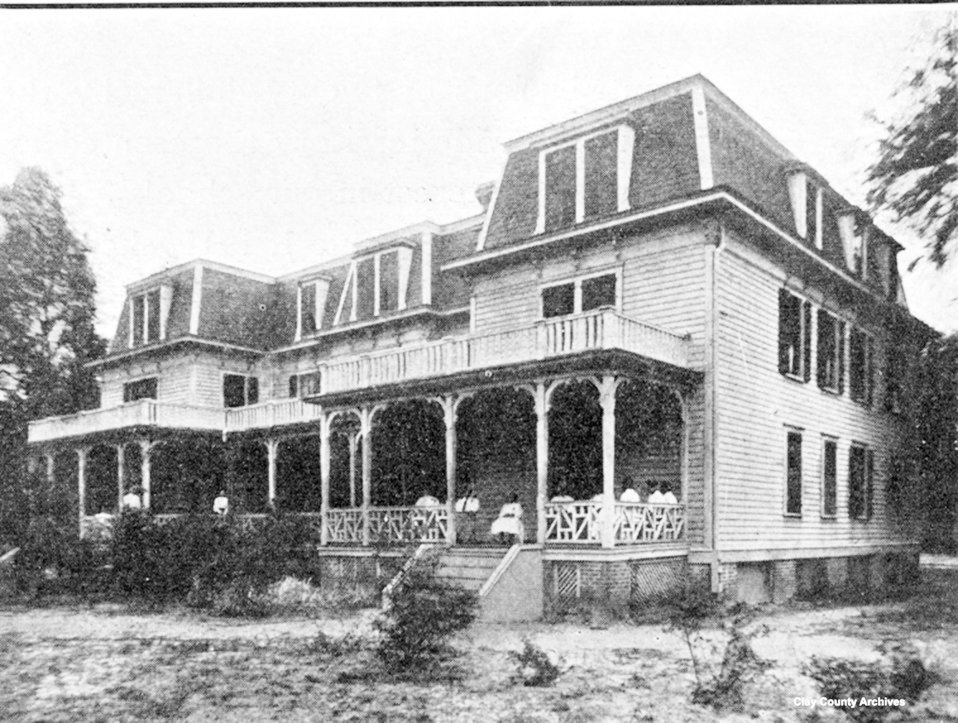

The Normal School once took up an entire block of Orange Park. It stood where the town hall now stands and covered about 10 acres.

What made the Normal School special was its students. The school …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

The Orange Park Normal and Industrial School

The Normal School once took up an entire block of Orange Park. It stood where the town hall now stands and covered about 10 acres.

What made the Normal School special was its students. The school taught both white and Blacks together, in the same classroom, with the same teachers. This was unacceptable to the segregationist William Sheats, the Superintendent of Public Education for Florida. He was going to make sure he rid Florida of that “vile nest of fanatics” as he called the school and its supporters.

Reconstruction had ended and in Florida, Democrats ruled. This meant black Floridians had fewer rights and a series of Jim Crow laws were put on the books. In 1888, the American Missionary Association opened the Orange Park school. AMA was a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded on September 3, 1846, in Albany, New York. The main purpose of this organization was to abolish slavery, to educate African Americans and other minorities, to promote racial equality, and to promote Christian values.

Originally, the school was to teach only black children but the fine quality of the education received there brought white children to the school. Children there received lessons in both the trades and in classical studies of languages, grammar, biology, mathematics, Latin, bible, American literature, history, bookkeeping, physics, English, geography, government and pedagogy (recitation, review studies and practice teaching). Trades were taught in sewing, woodworking, bookkeeping, cooking and other practical lessons. In addition, there was music, piano being at the forefront.

The students were able to live on campus. There was family life for the children outside of school hours, and there was church every Sunday. It was just a good school and ahead of its time in race relations.

Despite the Florida constitution requiring universal education Sheats wanted to create a law forbidding the teaching of white and Black people together in any way, place or time. In May of 1895, Sheats goal was realized with the enactment of a law making it illegal for any “individual, body of individuals, corporation or association to conduct within this state any school of any grade, public, private or parochial wherein white persons and negroes shall be instructed or boarded within the same building, or taught in the same class, or at the same time by the same teachers. “

Sheats wrote to a friend, “I want the AMA to keep hands-off in Florida.” Sheats got wind that the Orange Park Normal School has white teachers teaching Black students. He investigates further discovering that both races of students are taught together, live in the same dorms and even go to church together.

Indictments were handed down on April 6, 1896. Assigned the unpleasant task to going to arrest the teachers and headmaster, Sheriff James Elam Weeks was reluctant but did, as he had to do. He was arrested, B.D. Rowlee, principal, Edith Robinson, Helen S. Loveland, A. Margaret Ball, T.S. Perry, and O.S. Dickson. All were from either New York, Massachusetts, or Connecticut except Ms. Ball who was an Orange Park native. He carted them down the jail.

They quickly made a bond. The AMA hired top-notch Jacksonville lawyers, Horatio Bisbee and Clement Rinehart. The attorney’s legal strategy was a four-pronged defense: Asserting their 6th Amendment rights to know the charges and evidence against them they filed a motion to quash the indictments as being void for vagueness and asserted that their 1st Amendments rights of freedom of religion and freedom of association was being violated. And, as the 14th Amendment applied federal rights to the states’ they asserted that too.

Judge Rhydon Call heard the case. All of the charging documents and the motion to quash are available for public viewing at the Clay County Archives. Judge Call was progressive when it came to issues like the Sheats Law. He agreed with the Defense and by signing his name on the back of the motion and writing ”Granted” he dashed William Sheats’s dream of dismantling the Normal School.

The AMA and their supporters were ecstatic. The Northern papers carried the story far and wide, just as they had when Sheats first passed his law (they were appalled.) The teachers went back to teaching.

In 1913, the Governor approved an “Act Prohibiting White Persons from Teaching Negroes in Negro Schools.” This just put in place more laws against desegregated schools.

Rather than fight the law this time, the AMA chose to close its Orange Park school, which in the interim had suffered a fire (possibly arson) and reduced attendance by whites who had been scared away by all the trouble. When it closed in December of 1917 a noble experiment ended.

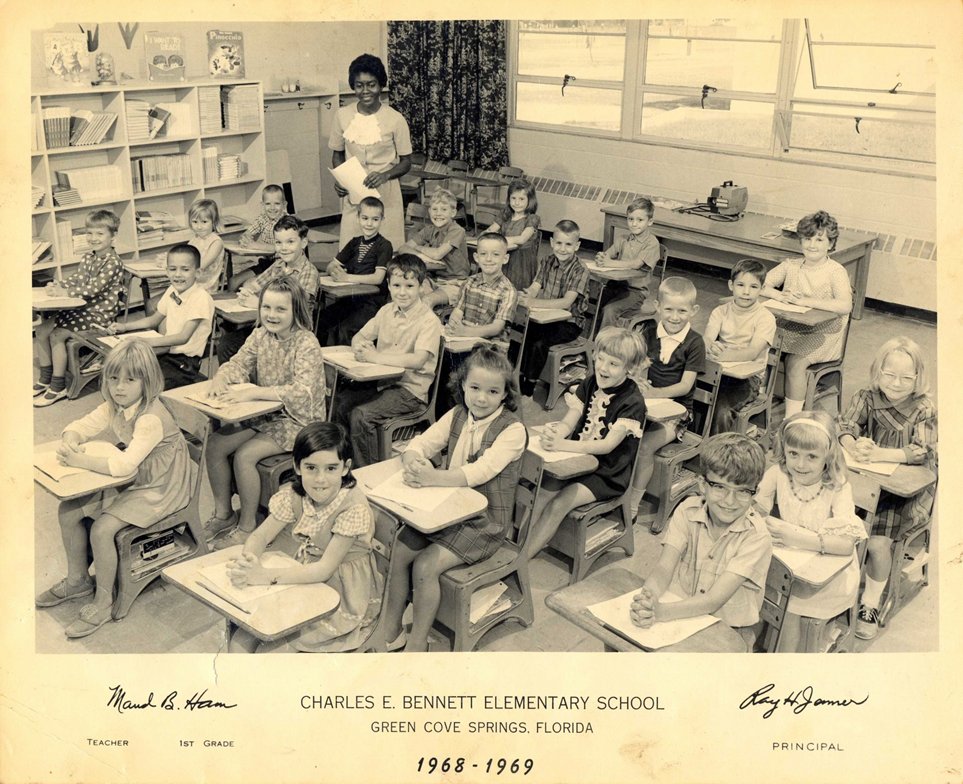

May 14, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court in Brown Vs Board of Education, stating, “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal …”

There is a historical marker for the school right next to Kingsley Avenue at the Orange Park Town Hall Park.