The Detention Center

jack@claytodayonline.com

More than 30,000 refugees were sent to Guantanamo Bay, a “legal no man’s land,” University of Miami Professor Michael Bustamante said. It isn’t formally U.S. territory and hasn’t been since …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

The Detention Center

More than 30,000 refugees were sent to Guantanamo Bay, a “legal no man’s land,” University of Miami Professor Michael Bustamante said.

It isn’t formally U.S. territory and hasn’t been since 1903 when the Platt Agreement was signed, which set the conditions for the U.S. to withdraw from Cuba and recognize the country’s new independence following the Spanish-American War.

One of the conditions was a perpetual lease agreement of a “coaling station” for about $4,000 annually. Since the Cuban Revolution in 1959, the communist government, as a statement of protest, declined every check the U.S. sent annually (except for one that was reported to have been cashed in by accident).

Steamships have been long discontinued, but the United States still maintains control of the base. The U.S. exercises jurisdiction and de facto control while also insisting that Cuba retains sovereignty.

“Full constitutional rights do not apply in Guantanamo Bay, as we have seen during the War on Terror. The refugees did not have access to due process for immigration proceedings. However, Cuban-American lawyers tried and failed to remedy this in a lawsuit at the time,” Bustamante said.

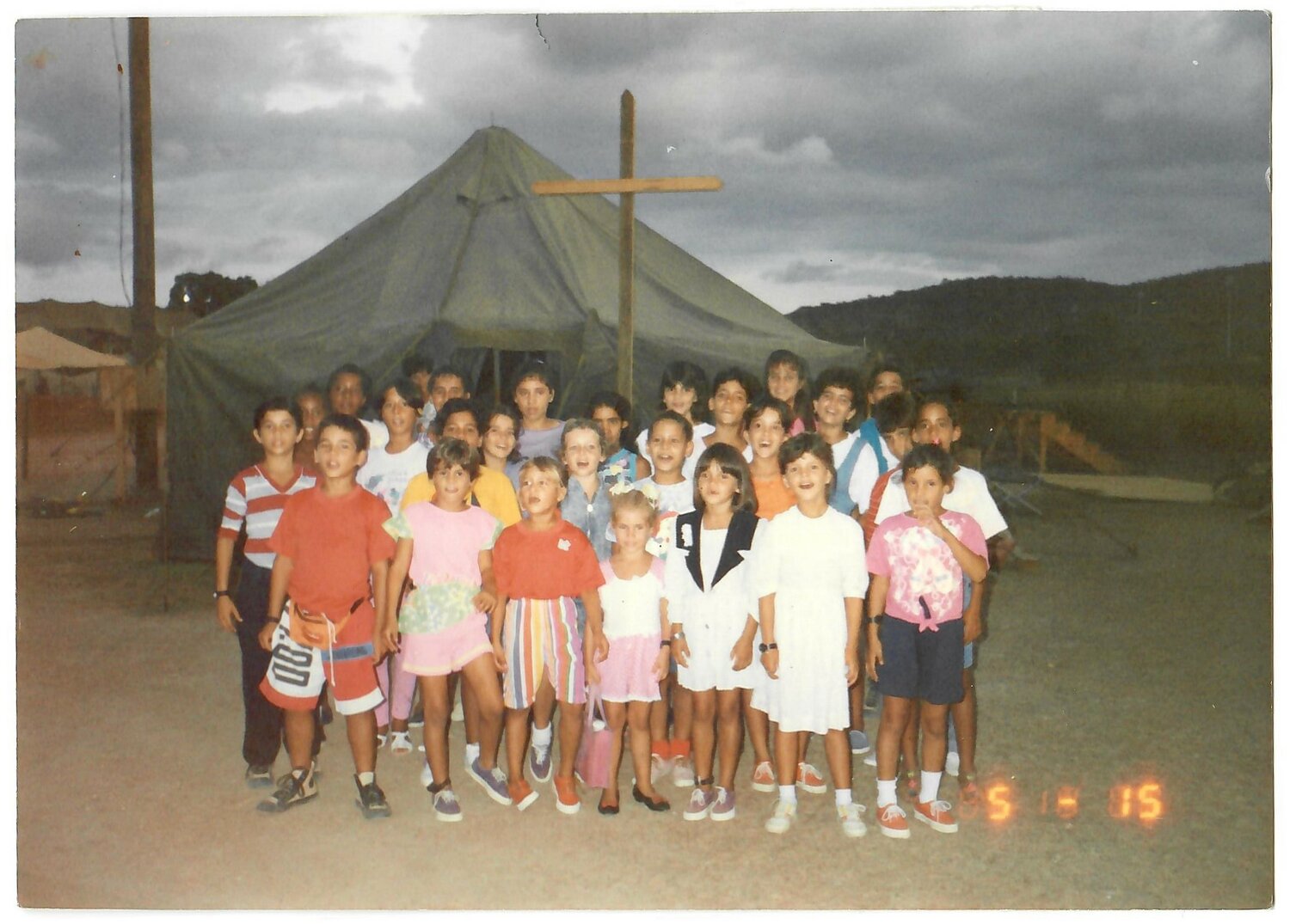

Celia shared slices of her childhood at Guantanamo Bay in her memoir: the sights, the sounds, the pain and even the small joys.

She empathized with the guards.

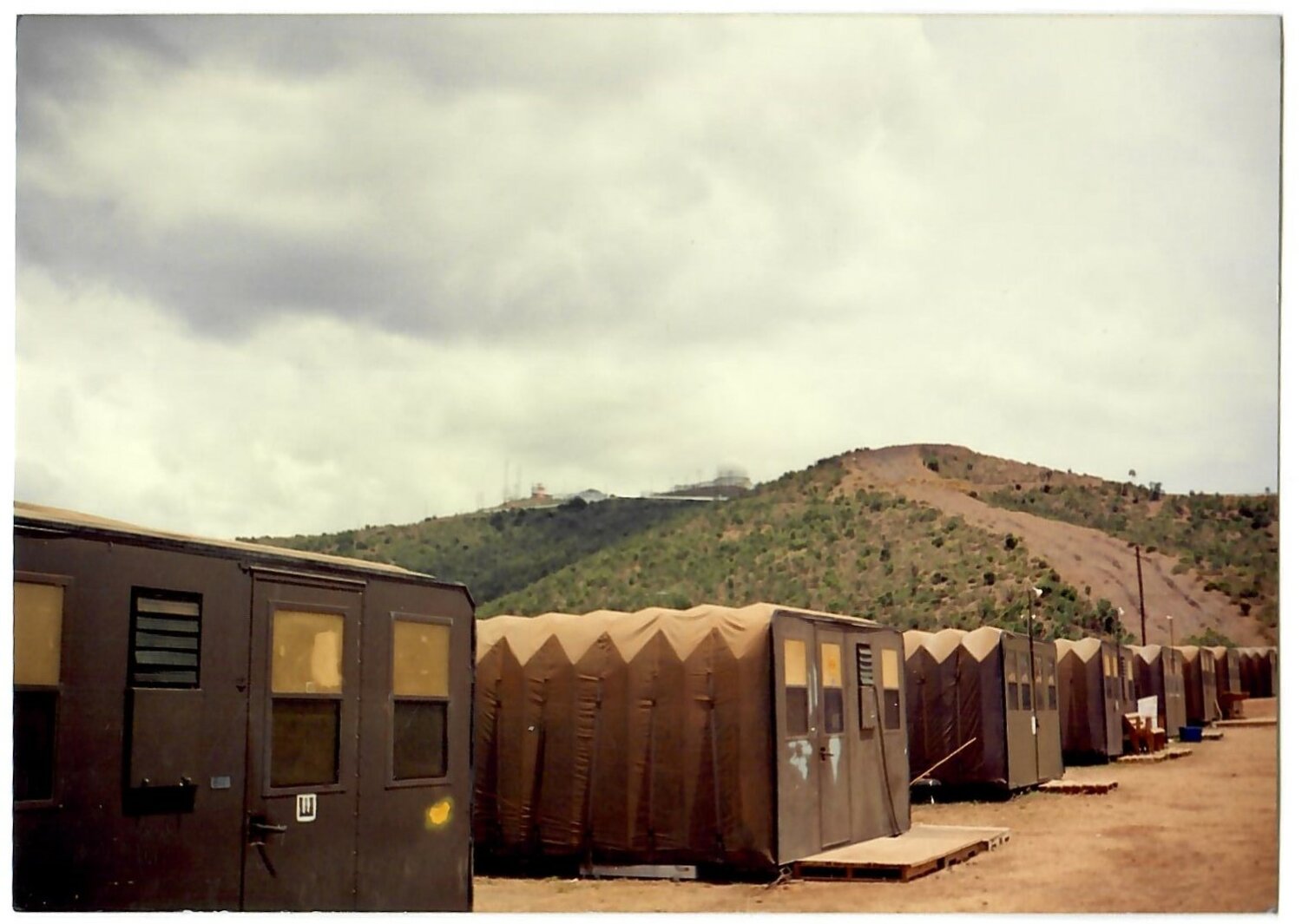

Tent camps were hastily erected. The U.S. officers scrambled about what to do. Celia was thankful for every meal, which was an improvement from the limited rations they received back home.

Celia said the guards tried to make the best out of the crisis. They went well out of their way to be accommodating, some even risking disciplinary action to bring extra supplies to the Ochoa family.

She was thankful for each act of kindness and disappointed in the other refugees for being so openly hostile.

“I do think the conditions were not ideal or acceptable. The camps eventually got better, but still, the refugees were treated more like a threat to United States security than like refugees,” Guerra said.

The refugees confined at the base had no idea what would happen to them. They couldn’t leave. They couldn’t call home.

At its most significant peak of confinement, it is estimated the camps held more than 30,000 Cuban and 30,000 Haitian refugees.

In 2023 and living in Middleburg, Celia self-published her memoir. As a courtesy to Clay Today, she shared a meticulously curated photo album, which included many photos within her memoir. Fittingly, she is the co-owner of Center Shot Selfies, a photo booth rental company.

On March 15, Celia worked at her photo booth at a Jacksonville Icemen hockey game. Tanya Lea and a friend approached the photo booth and posed for a few photos.

Lea asked about her photo booth business and the events they cover.

“I told her we do weddings and birthdays, and I recently ventured into unique events such as book signings. As I was an indie author, I would bring the booth with me to these events. Naturally, she asked what my book was about. She ordered my book on the spot,” Celia said.

Of course, part of Celia’s experience as an Ochoa and a refugee involved a stint at Guantanamo Bay from 1994 to 1995.

Lea was at Guantanamo Bay during the 1994 Cuban Rafter Crisis. The realization dawned on her.

“Oh my god, I fed you!” Lea said.

Next week, the two suddenly realized they were on the opposite side of the security fence at “legal no man’s land” at Guantanamo Bay. And yet, they prevailed to find common ground 30 years later.