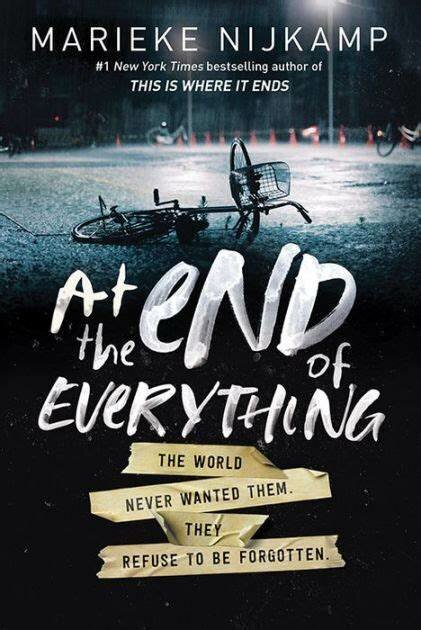

'At the End of Everything' by Marieke Nijkamp

Bruce Friedman leads the nation in submitting book challenges. At the last school board meeting, he brought forth a challenge of a new kind.

"If you don’t address (the most egregious appeals of books still in circulation) promptly, I’m going to do them one book (at) a time by calling the press. And I’ll put all of your names in the story, and the title, and the author, and we’ll let the community decide,” Friedman said.

"At the End of Everything" by Marieke Nijkamp begins with a content warning before the story starts:

"This book deals with ableism, abuse, death, illness and implied eugenics, imprisonment, transphobia... assault, blood, gunshots, racial profiling, and sexual violence."

Acknowledging and flipping past that, the young adult novel "At the End of Everything" follows the perspective of three children – Logan, Emerson and Grace – at a fictional juvenile rehabilitation center. Logan is autistic and nonverbal. Emerson goes by they/them pronouns.

They, and the other children enrolled at the rehabilitation center, discover all the guards have suddenly vanished. After being left behind during the onset of a national pandemic, the children work together to survive a deadly, contagious plague all alone in the deserted rehabilitation center.

Imagine "Lord of the Flies" by William Golding if the setting took place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like "Heroine" by Mindy McGinnis, this is a book has been challenged, reapproved by a book review committee and placed back on the shelf for high schoolers. Bruce Friedman has appealed that decision, which is how the procedure for book challenges works currently. Although, that may be subject to change in the new media policy for Clay County District Schools.

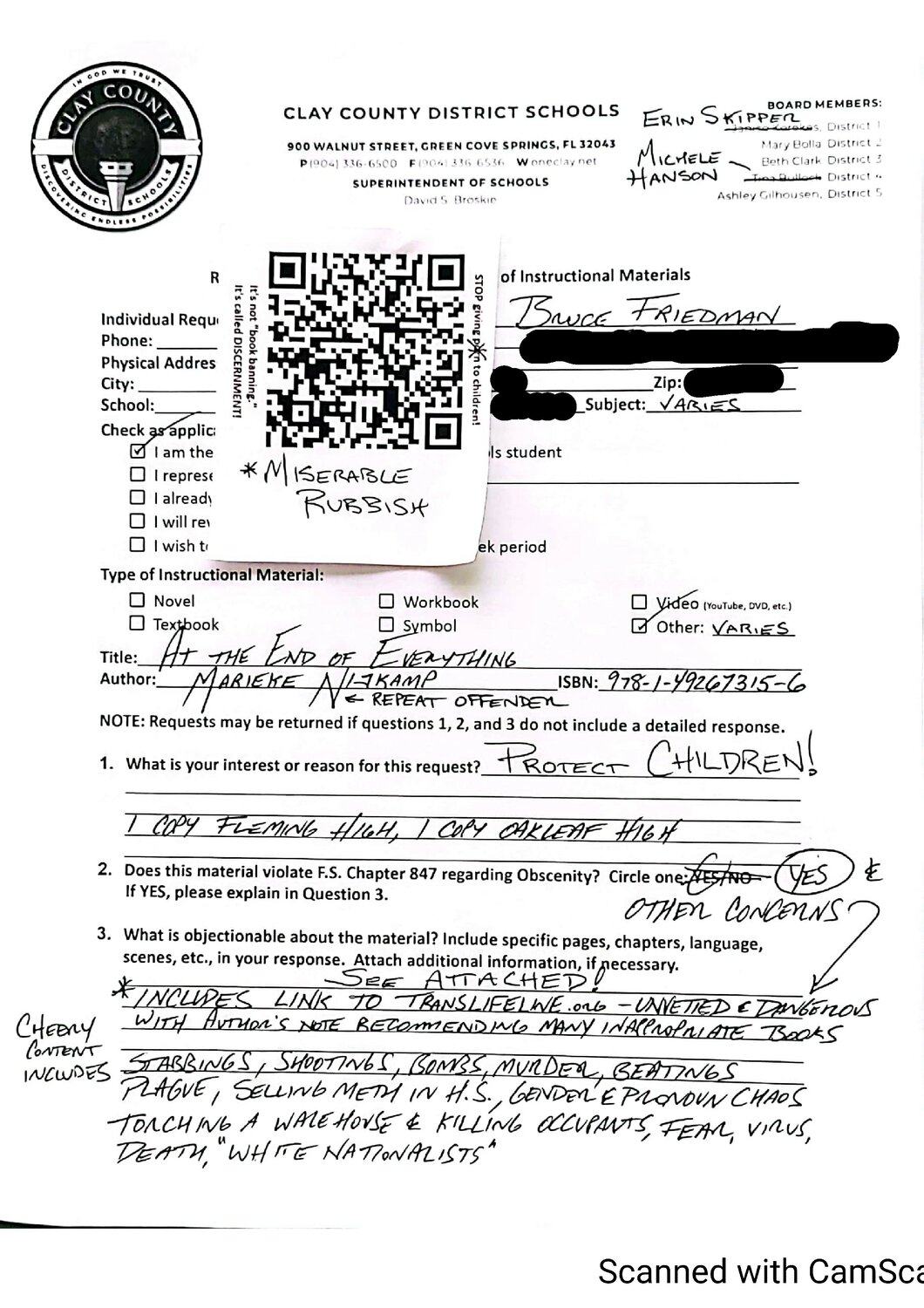

Friedman provided the challenge form he originally submitted, and he points out some additional “cheery content.” This is his challenge form:

2023_053023_At the end of everything by Marieke Nijkamp_complete challenge.pdf - Google Drive

Characters drop the f-bomb in this book. There are a few implied references to sexual assault, although not graphically. The content warning before page one is not lying, and Friedman’s challenge isn’t entirely wrong – I couldn't find an example of "White Nationalism" and I did not find the presentaiton of a nonbinary character "indoctrination."

It raises the question: is including a nonbinary perspective "indoctrination" as Friedman would argue, or does it capture "the broad racial, ethnic, socioeconomic and cultural diversity of students?"

I also want to mention that Friedman did not approve of the links and related readings at the end of the novel. He submitted challenges to all the related readings except one (“Just Mercy: A True Story of the Fight for Justice” by Bryan Stevenson, which Friedman said was “OK.”) and two others which were not currently in in school libraries.

“Have you vetted every link on this website… No!” Friedman wrote on his challenge, referring to translifeline.org.

I cannot comment on the related readings because I have not read them.

While "At the End of Everything" is decidedly not pornographic, I'm actually in a tougher spot than where I was last week with "Heroine."

There was a lot I liked about "At the End of Everything." For starters, I found the premise interesting.

I thought the autistic and nonbinary representation was done in a respectful way. The rehabilitation center enrolled “delinquent” children: those convicted of crimes for just and unjust reasons and those who are culturally deviant, such as Emerson running away from home for being nonbinary. Regardless, these children were treated the same way: poorly.

(Friedman responded: "'Respectful??' Is it respectul of DNA? Conservative loving parents? Religion? Florida public school toilet policy? I don't find it respectful at all.")

I think this was an intentional choice by the author to demonstrate how society views delinquency in children and how it attempts to address it.

I agree with the central point of the book’s “thesis.” Instead of judging others for what they did, we should attempt to understand why. I agree forgiveness is a virtue, and it’s a virtue that is commonly discarded during a crisis.

This is why I was disappointed at the epilogue, which throws that message into the wind. I have a few other qualms. As a Catholic, I didn’t find Emerson’s conflict with the Catholic Church offensive – I just found it distracting and out of place, since it didn’t contribute much to the narrative. Throughout the book, I found the writing style simplistic and even myopic during certain chapters. The content is easy to digest, at least. Truth be told, I don't know if readers at a high school level would get much out of this entry.

The real debate surrounding this book is whether or not it should be acceptable for middle school.

During the open forum last Tuesday, School Board Member Michele Hanson used the word "spicy" to describe books like this – books that toe the line (or surpass it in some instances) of what is typically acceptable for the target demographic.

Everyone who attended the open forum shared the common ground that pornography should not be in libraries. However, some books address the real-life issue of sexual assault – sometimes graphically, sometimes not. Some books detail drug abuse and addiction (“Heroine” by Mindy McGinnis) – sometimes in detail, sometimes not. Many of the “spicy” books use “foul language.”

As I read through “At the End of Everything,” I imagined myself in middle school. As I set the book down, I imagined myself leaving it for a student in middle school, today. Unfortunately, it is impossible to know for a fact. Could a child enjoy this book? Could a child be scarred for life? I'm leaning toward the former, but every reader is different.

During the open forum, I heard a collective interest in developing a rubric that would objectively evaluate books by a set of concrete standards for various age groups.

For example: “Heroine” is not pornographic and does not violate FS 847, but it drops the f-bomb a few times and chronicles drug use through a lens of dramatic irony that may not be obvious to young readers. I think most parents understand the book is a powerful cautionary tale but would still prefer it in a high school library.

I think “At the End of Everything” is a textbook example of a “spicy” book that would slip into the chasm which divides middle school and high school. It’s currently approved for high school, and I expect it will stay there. However, as the school board works to develop a new comprehensive policy, I expect it will not make the cut for middle school. That’s my gut feeling.

I think this is unfortunate because I would’ve enjoyed this entry if I were a middle schooler.

I think this book demonstrates the challenge of developing a comprehensive rubric. Even with movies, there can be a lot of variation within the “PG” and "PG-13" categories. Also, novels are typically longer than movies (the audio book for “At the End of Everything” is nearly 10 hours on Spotify), so it’s harder to get a gauge on the context.

Friedman posed a question to me: would it be acceptable to restrict this novel for middle school until a student turned in a signed permission slip from a parent or guardian?

If I were designing the new media policy, I would say “no.” The book raises some interesting points – some of which I don't agree with – but I don't think that alone warrants this book special treatment or censorship.

I think individualized permission slips for books on a case-by-case basis would only overwhelm the media specialists further. For “At the End of Everything” in particular, there are admittedly some “spicy” moments. But it provides ample warning before the first page. I am under the impression middle schoolers would have the thought process to either put the book back on the shelf or continue reading (Maybe content warnings will be the norm in the new media policy).

As a community, we’re going to have to decide this together. When we draw lines in the sand, should we do so based on the complexity of the writing itself? Or should we implement a “three strikes and you’re out” approach to explicit content: f-bombs, sex jokes, drugs, etc.? Should we – as Friedman recommends – err on the side of caution? If we even have to think this hard about a book, wouldn’t it be better off gone?

Or is analyzing content part of what makes reading a book such an interesting and meaningful endeavor?

Reach out and let me know what media policy would be most beneficial to children in Clay County District Schools.

For next week’s Bruce Friedman’s Book Club, we will be reading a challenge in progress – not an appeal. If a statement is developed during the school board workshop on Jan. 23, we can apply those standards to next week’s novel. In a way, it would be beta testing the policy before the vote at the next school board meeting in February.

“It will be a nasty one. Probably requiring some careful editing,” Friedman said.

Next week's read will be "Imaginary Friend" by Stephen Chbosky. According to Destiny, the school library database, this book is at an "adult" interest level and is accessible at Ridgeview High (and, as of now, it's currently checked out or removed).