‘Heroine’ by Mindy McGinnis

jack@claytodayonline.com

“Heroine” by Mindy McGinnis begins each chapter with a dictionary definition, so I thought it would be fitting to do so here. “Heroine” is a fictional young adult novel that chronicles the slow, tragic descent of Mickey Catalan toward opioid abuse...

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

‘Heroine’ by Mindy McGinnis

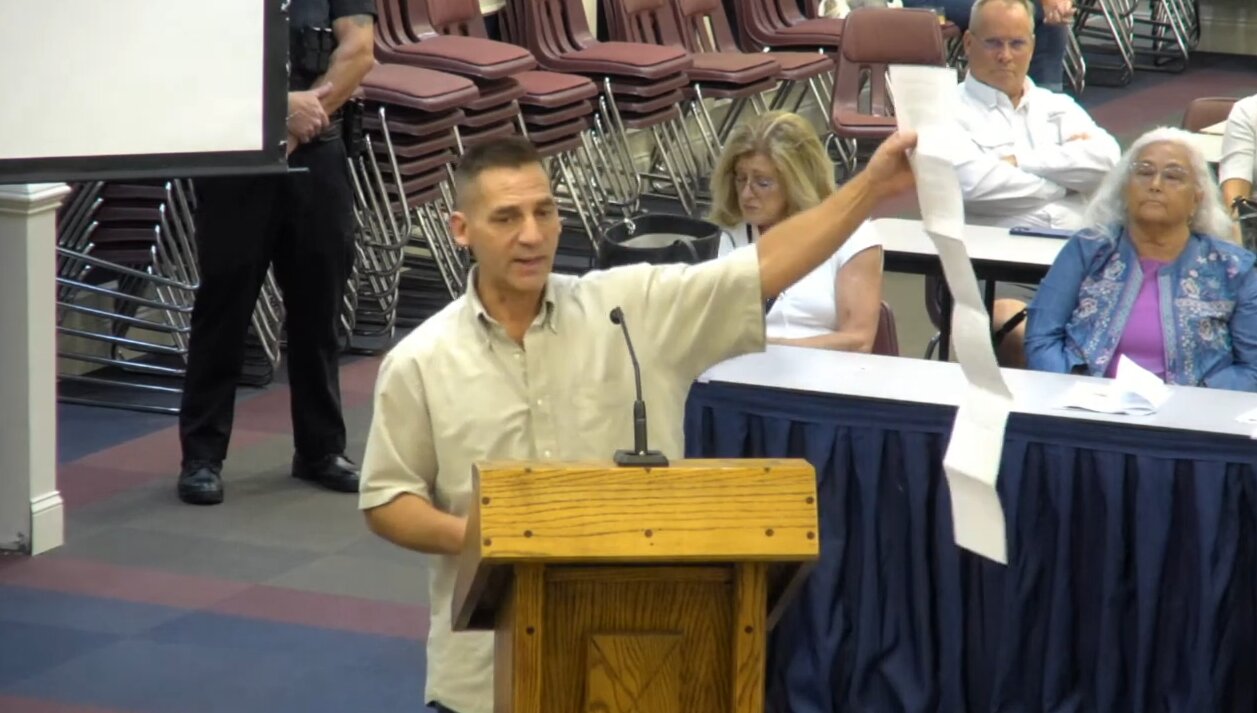

This is a three-part editorial series where I navigate the multiple sides of the Clay County “book ban” debate. Bruce Friedman leads the nation in submitting book challenges. At the last school board meeting, he brought forth a challenge of a new kind.

“If you don’t address (the most egregious appeals of books still in circulation) promptly, I’m going to do them one book (at) a time by calling the press. And I’ll put all of your names in the story, and the title, and the author, and we’ll let the community decide,” Friedman said.

pornography: printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, intended to stimulate erotic rather than aesthetic or emotional feelings

“Heroine” by Mindy McGinnis begins each chapter with a dictionary definition, so I thought it would be fitting to do so here. “Heroine” is a fictional young adult novel that chronicles the slow, tragic descent of Mickey Catalan toward opioid abuse, addiction and then physical dependence. It all begins with a single prescribed pill.

The faux justifications, the cognitive dissonance, the side effects, guilt, withdrawal, death. The book illustrates each step down the dark staircase of addiction. The book argues that dependence can happen without the user even realizing it. Dependence can befall anyone. Similar to “Go Ask Alice” by Anonymous, “Heroine” doesn’t pull any punches to make its point.

“Heroine” is at the precipice of a new wave of appeals submitted by Bruce Friedman, who has led the crusade to remove pornography from school libraries.

Friedman’s challenges are successful when he invokes FS 847. Books “depicting nudity, sexual conduct, or sexual excitement” without “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors” are in violation of FS 847 and, therefore, are yanked from the library shelves of public schools.

Last year, a book review committee decided that “Heroine” has not violated FS 847. Therefore, the book has been placed back on the shelf. Therefore, Friedman submitted an appeal.

When Friedman brought his “new challenge” to the press, I checked the book out from a Clay County public library (not a school library; I am not a student) to read over the weekend. With a tight deadline, I even listened to some chapters from the audiobook on Spotify while driving or jogging.

I read and listened and waited for all the pornography that I was anticipating, but never appeared.

What I found instead was a powerful, cautionary tale illustrating just how easy it is to try to justify addiction. How quickly it takes to lose control. How quickly narcotics replace happiness from everywhere else in life. How opioid addiction hurts families. How opioid abuse kills people.

This is me, a member of the press, upholding that decision of the book review committee.

“Heroine” is anything but sunshine and rainbows, and explicit language is frequently used. It is admittedly a tough read, but that’s the point. “Art is meant to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable,” as the saying goes.

The only way to stop the opioid epidemic is to show the next generation exactly the false pleasure they can expect and the true pain that will follow. If we are serious about ending the opioid epidemic, we need perspectives from books like “Heroine” in public school libraries.

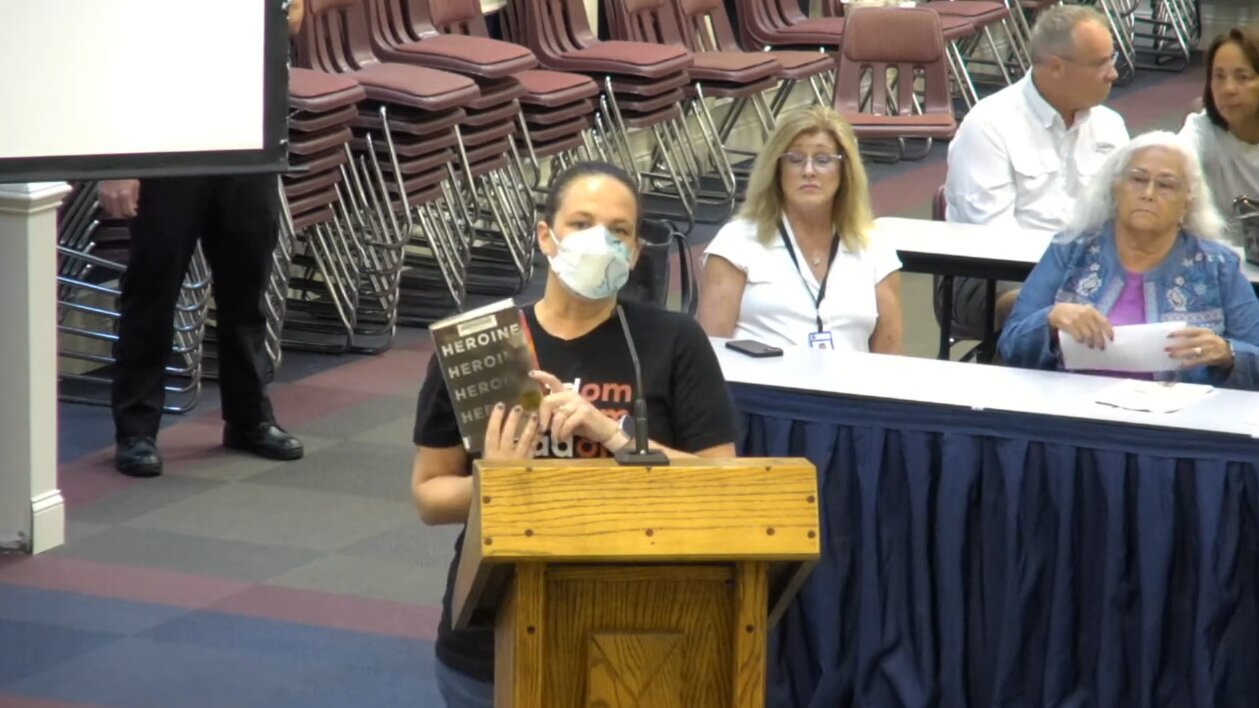

One resident from a school board meeting in October put it better than I did.

“No teenager is going to read this book and at the end say, ‘You know what? I think I really want to use some heroin now.’”

Specifically, Friedman had a grievance with two passages he read out loud at a school board meeting:

“Can I rub your back? How about your vagina?” which is said by Bella Center on page 29.

“‘I’m even better at scanner codes than I am at blow jobs,’ she says, sucking on her fork,” which is said by Josie on page 127.

However, in the context of what’s on the page, these are understood among the characters to be crass jokes. Both Bella Center and Josie are lightly reprimanded in the following sentences.

I agree with Friedman that pornography should not be in school libraries. There’s a famous quote by a Supreme Court Justice, “I know (pornography) when I see it.” I read and listened to “Heroine,” and I just didn’t see it.

I reached out to Friedman expressing that view. Friedman admitted that he is “NOT calling ‘Heroine’ porn” but that “age appropriateness is the issue at hand.”

According to a District Reconsideration List, “Heroine” is listed as “No violation of Florida Statute, Remain in Collection Keep: HS (High school) Only.” I agree that this is a book high schoolers can resonate with.

I think it is OK to be perturbed by some of the content of “Heroine.” You’re supposed to be. But that alone is not a legal or moral justification for removing this story from the thousands of high school students in Clay County public schools.

At that same school board meeting in October, Friedman’s microphone was silenced when he attempted to read a passage from “Heroine.” He was then calmly escorted out of the auditorium by two police officers.

I’m no lawyer, but HB 1069 states “parents shall have the right to read passages from any material that is subject to an objection. If the school board denies a parent the right to read passages (from the material), the school district shall discontinue the use of the material.”

I asked Friedman what this means to him since “Heroine” is still in circulation. I asked him if he is debating legal action.

“I only intend to sue if given no options. I have a few remaining. Your future weekly efforts included,” Friedman said.

I asked him if he would still press forward even though the costs of litigation would fall upon the Clay County District Schools, funded by taxpayers.

“As to legal costs (between my own expenditures and those by CCDS). Costs are irrelevant. Who pays is irrelevant. Protecting the innocence of America’s children (is) priceless.”

I’m not sure what direction the “book ban” debate will take, especially with the open forum scheduled on Jan. 16 at Orange Park High at 6 p.m. I’m not sure what the costs or outcome of any litigation would be either. Again, I’m not a lawyer. What I do know, if you are a concerned parent, you have the option to withhold your signature from the media permission slip. You have the option to homeschool. You have the choice not to read books in public school libraries.

But you shouldn’t make that choice for other parents and their families.

In next week’s Bruce Friedman’s Book Club, we will be reading “At the End of Everything” by Marieke Nijkamp. Like “Heroine,” this book was challenged, upheld and placed back on the shelf. We’ll decide together as a community if that was the right call. Send me an email, and I’ll try to include your thoughts in the article. Students, feel free to read and follow along for next week’s discussion – while you still can.